Christine Nguyen: Rock Paper Salt

July 10 – September 5, 2010

Huntington Beach, California

catalog

The Love Life of A Salt Crystal

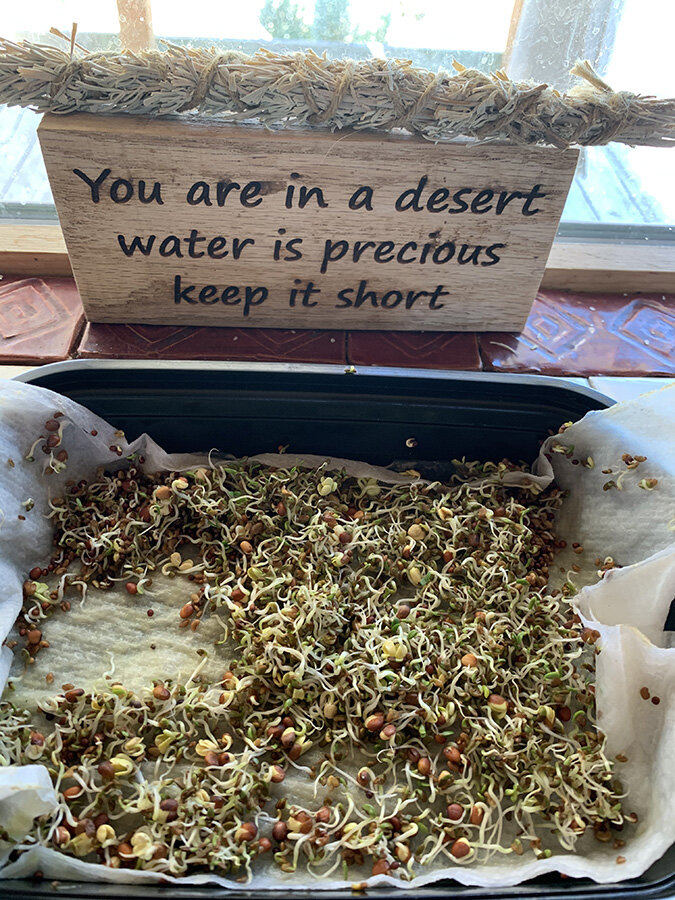

If you visited her studio five years ago, you may well have had a different experience viewing Christine Nguyen’s work than if you go there today. Back then you would have seen photographs of drawings, stacks of Mylar sheets, paints, inks, pens, and pencils. Nowadays, her apartment looks more like a science laboratory than an artist’s studio. The art materials are still there, but experimental projects with salt, borax, and algae growing on them are scattered everywhere. Over time, Nguyen has developed ways of working on paper and with objects that draw attention to her closely controlled processes. Absorbed, meditative, rapt in visualizations siphoned from some of her earliest memories, the tremendous accumulation of past advancements in the arts and sciences also inspires her. Although she has always been fascinated by nature, two different environments, the sea and interstellar space are of special interest. Her artworks are windows to ideas in progress, potentiality that resides within the artist who is always seeking a new boundary to navigate and cross. Changes in her production have occurred incrementally, the result of gathering numerous concepts, hunches, and experiences over a long period of time. And there was always more to come, always something new to discover in her work.

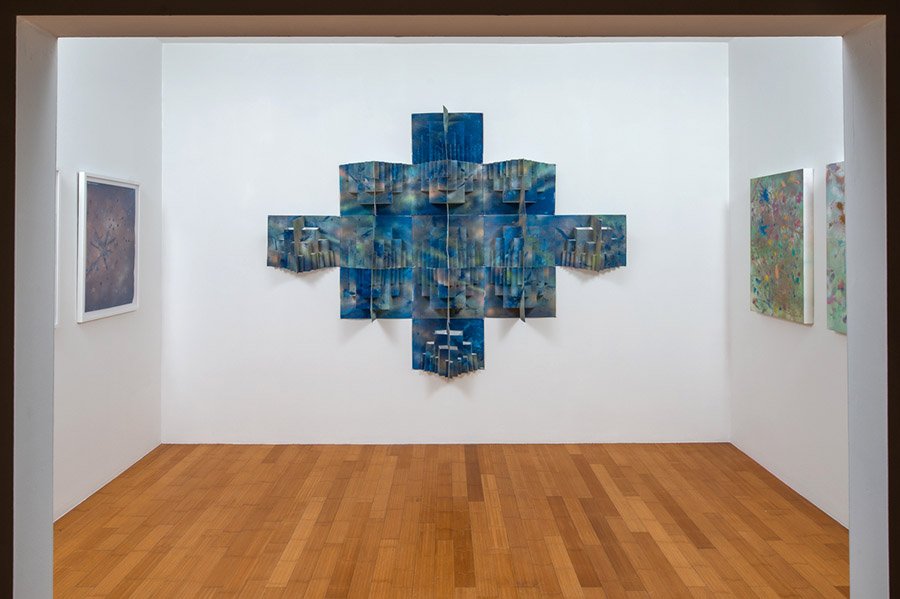

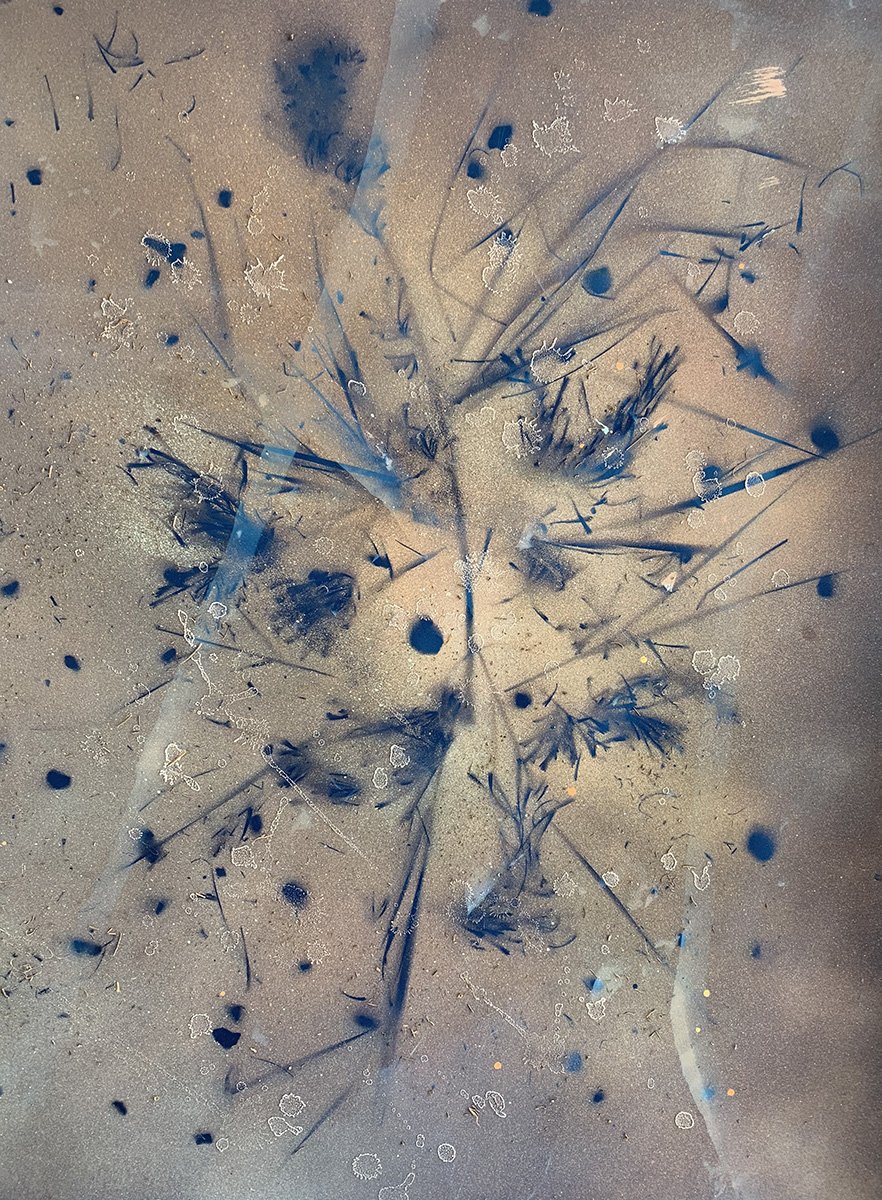

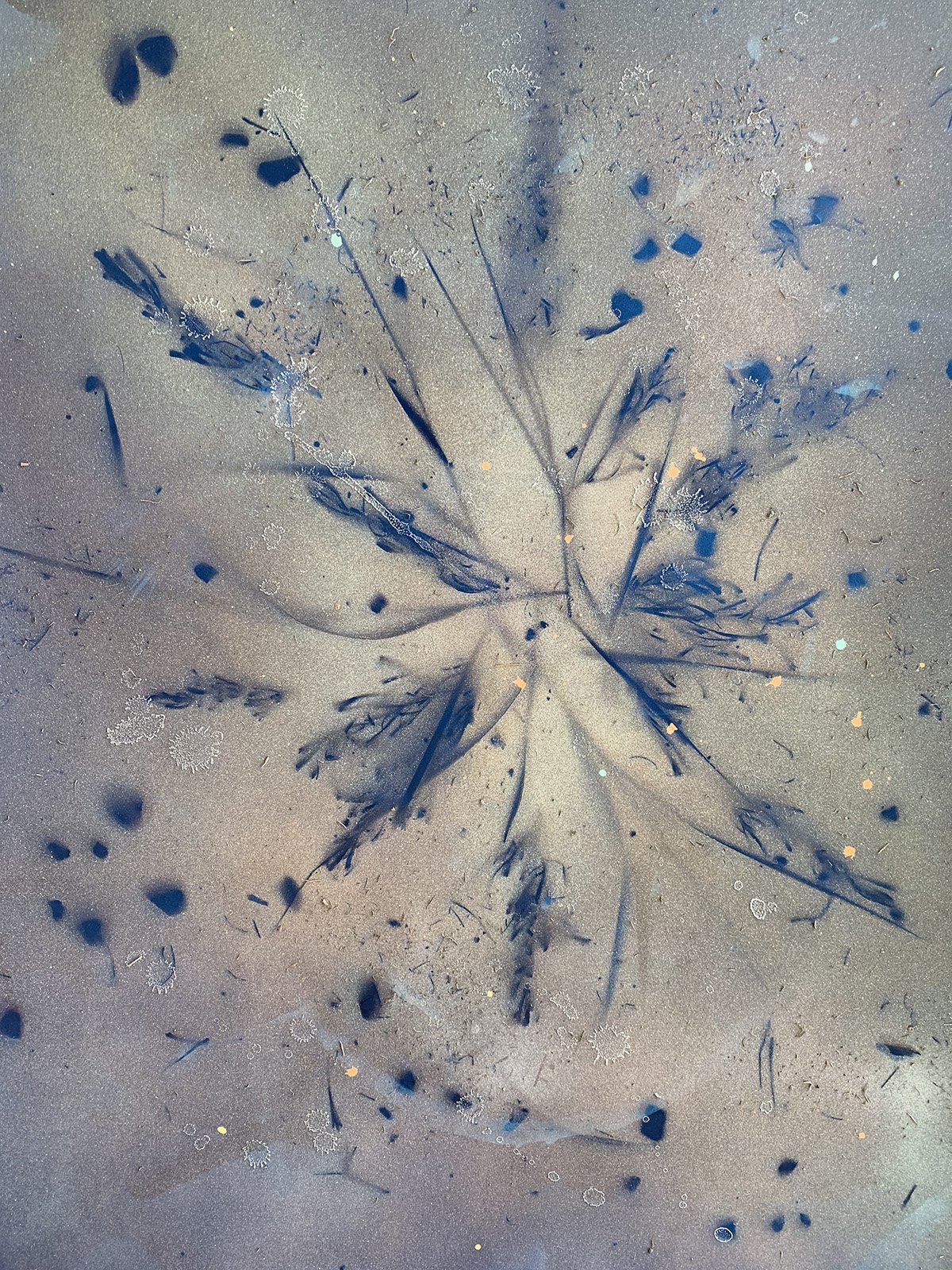

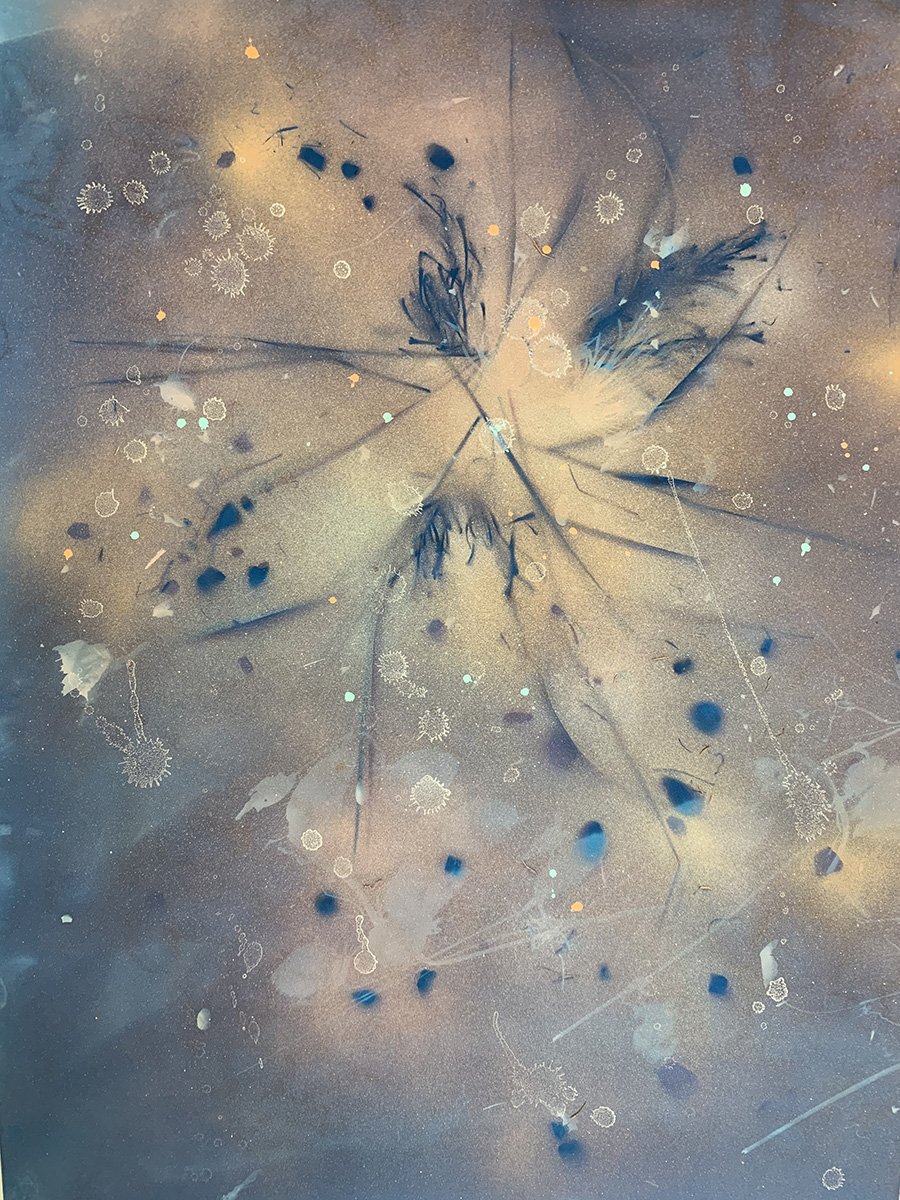

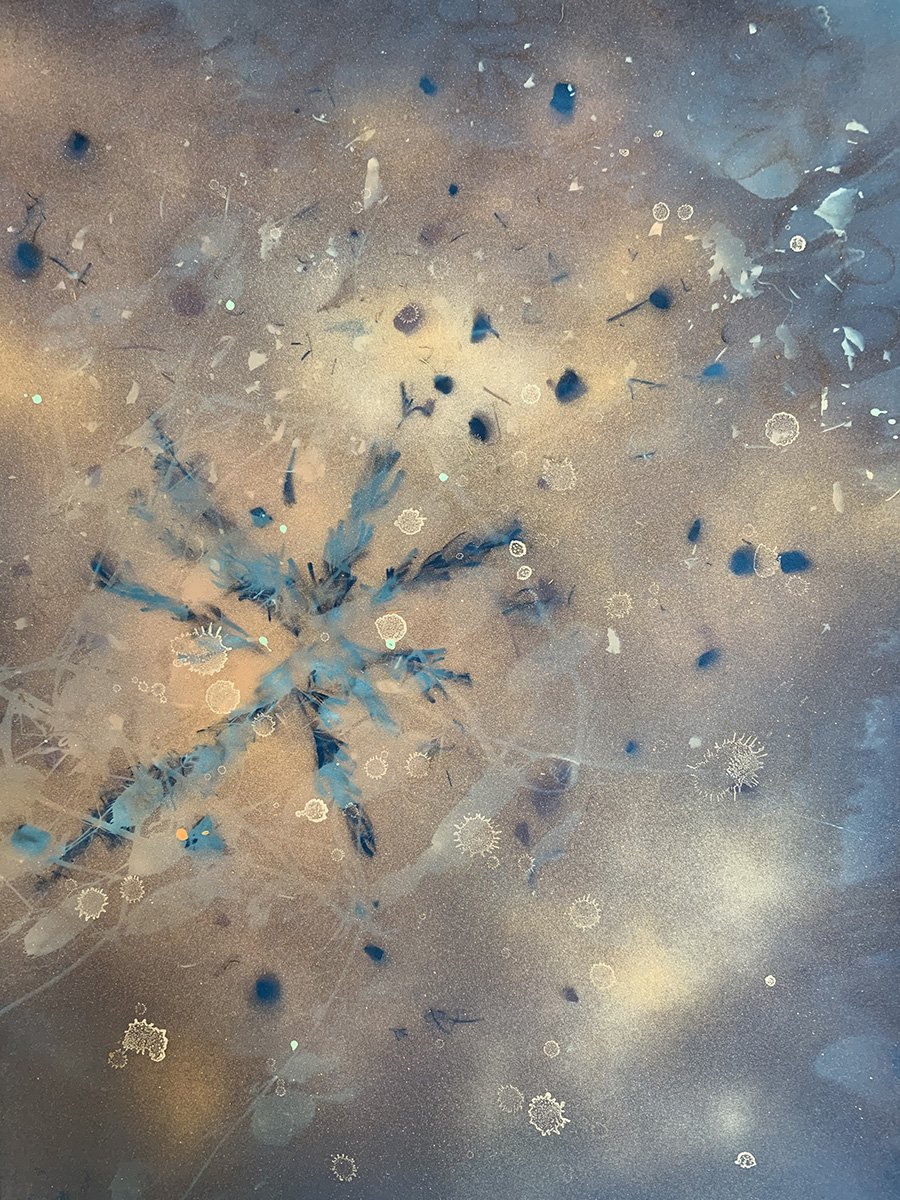

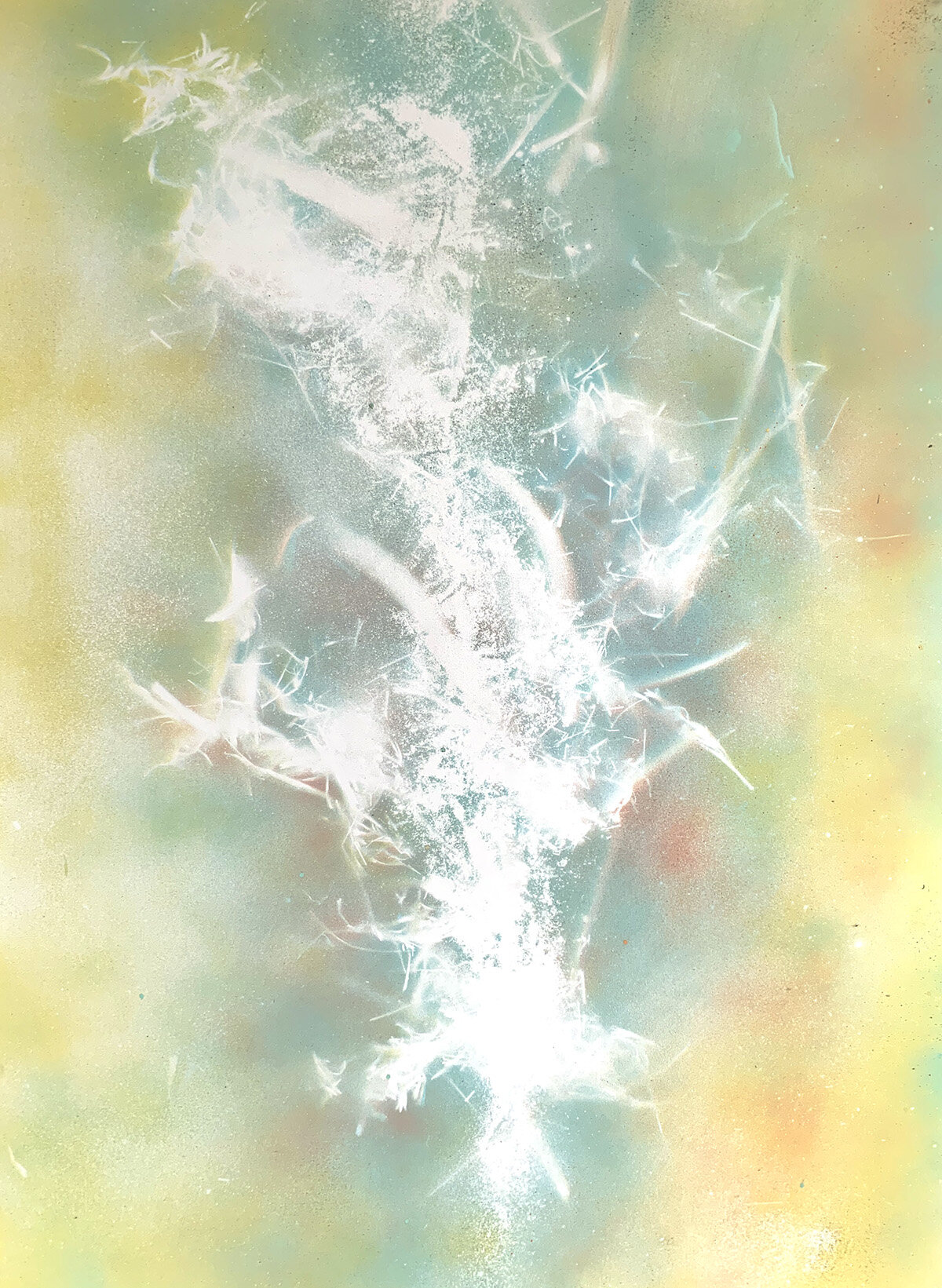

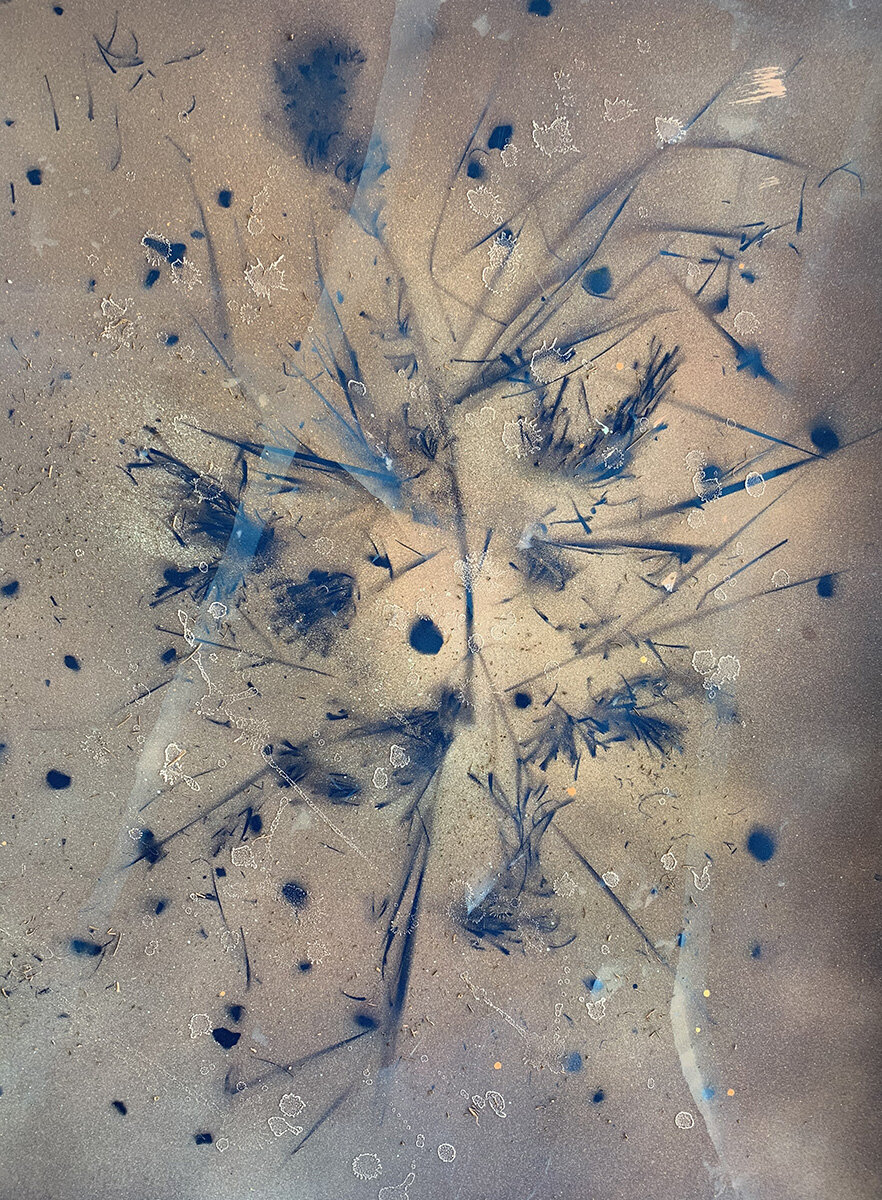

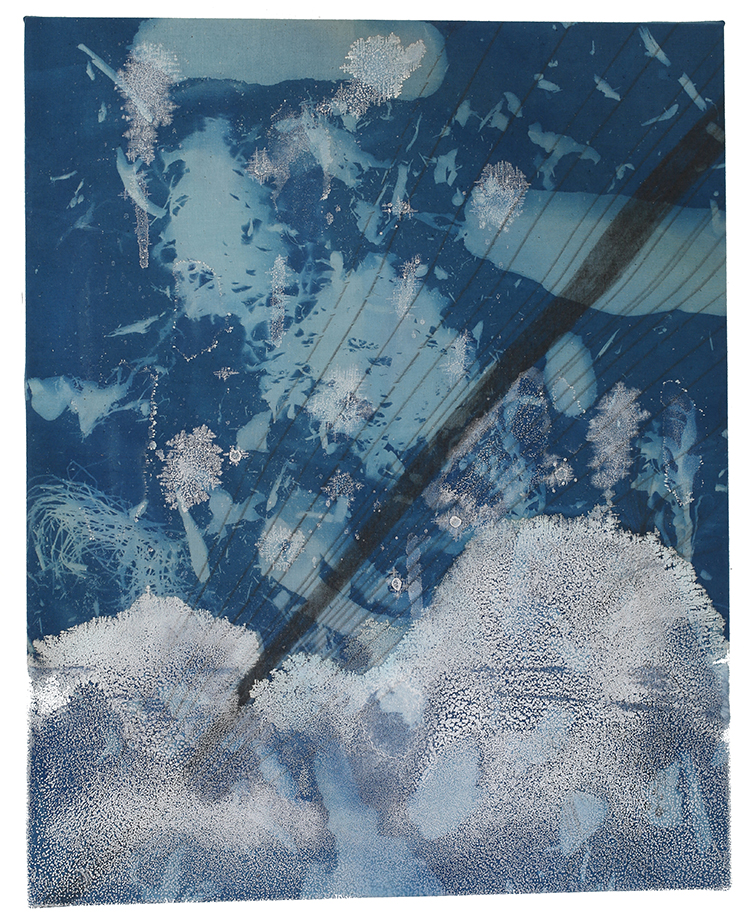

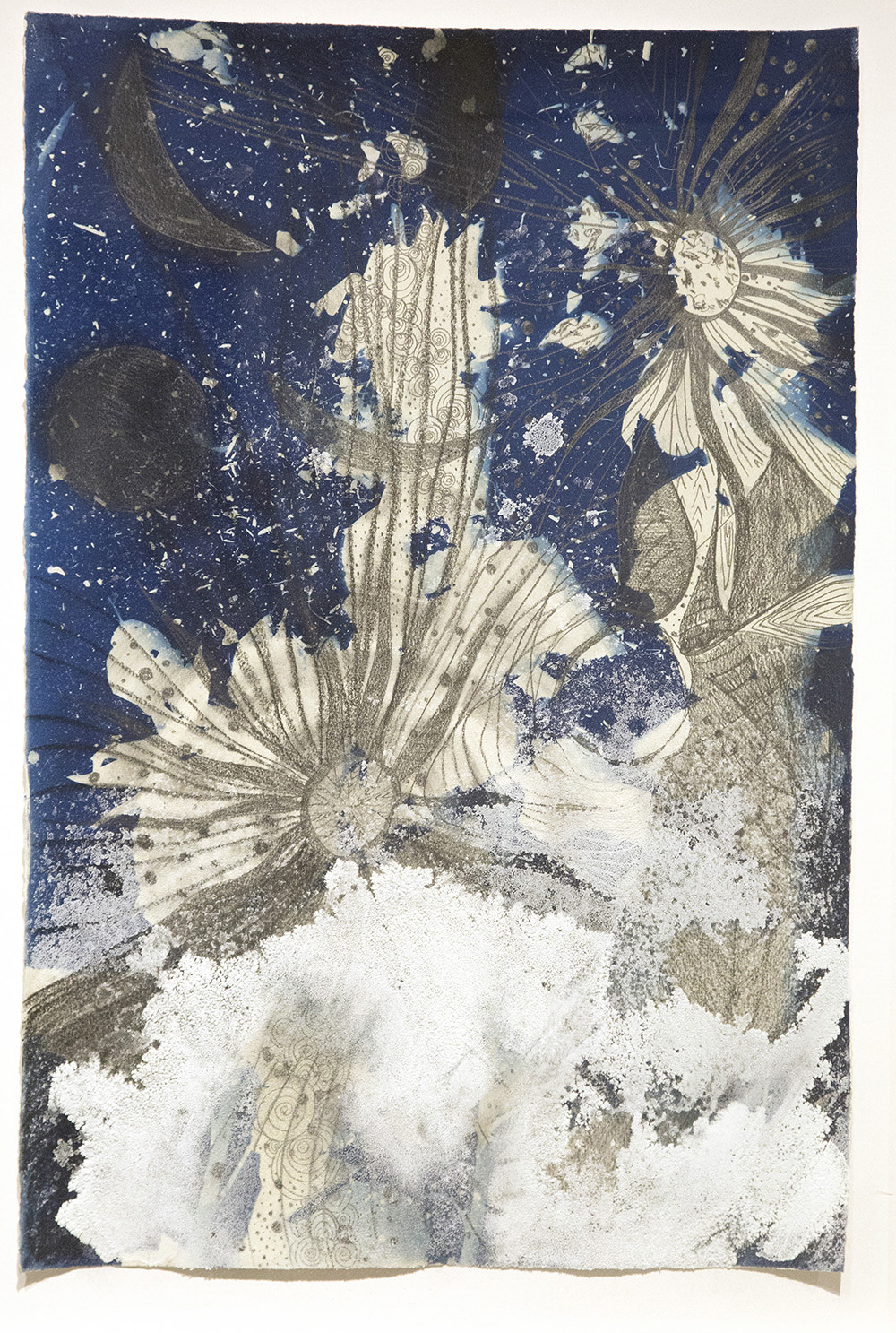

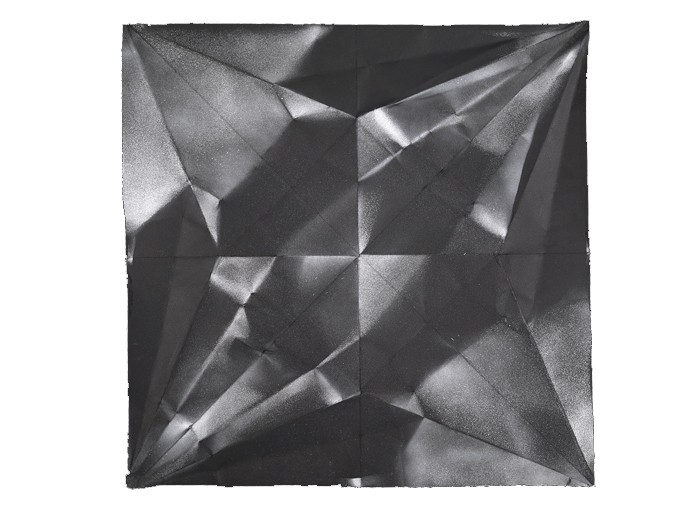

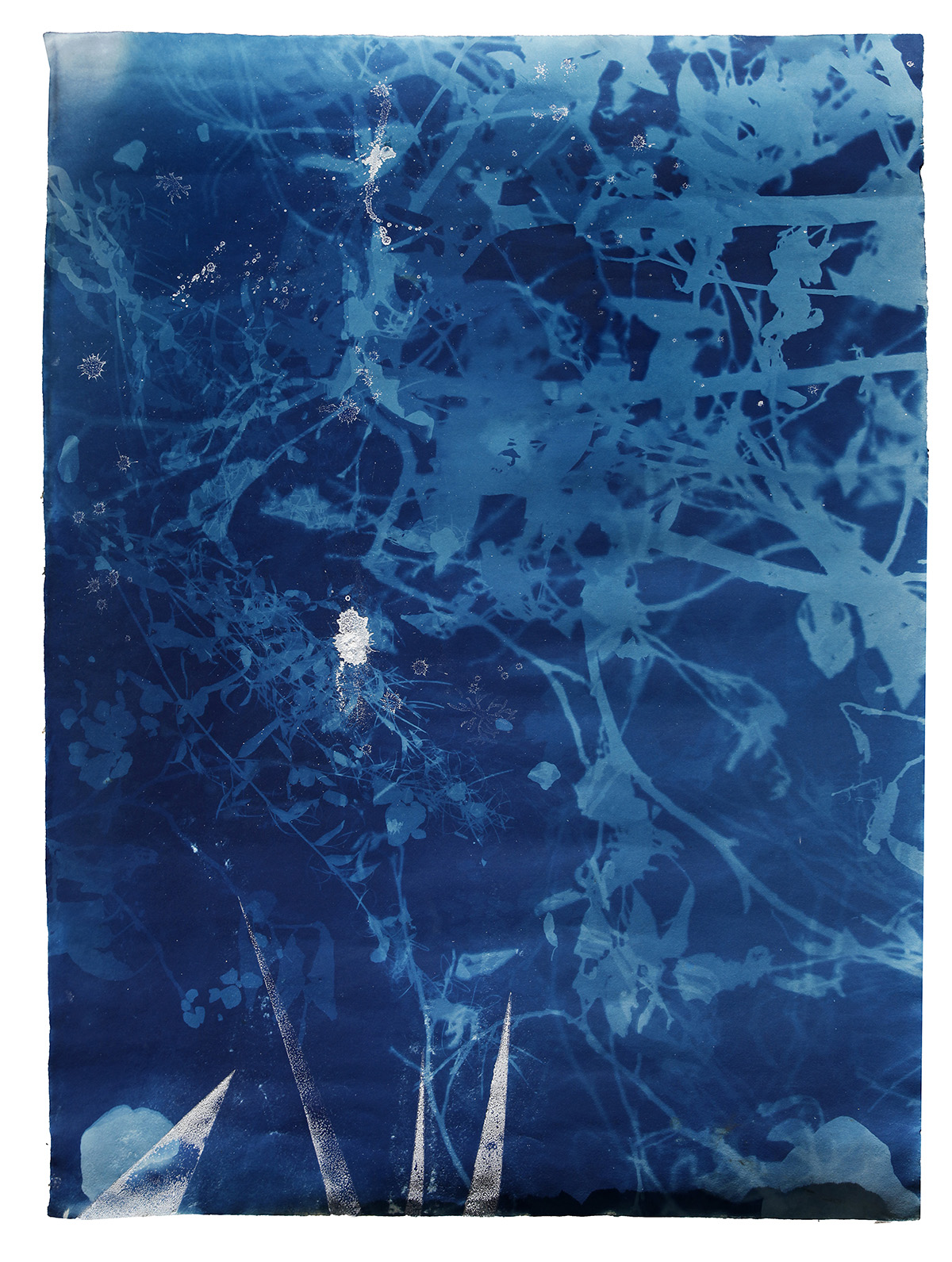

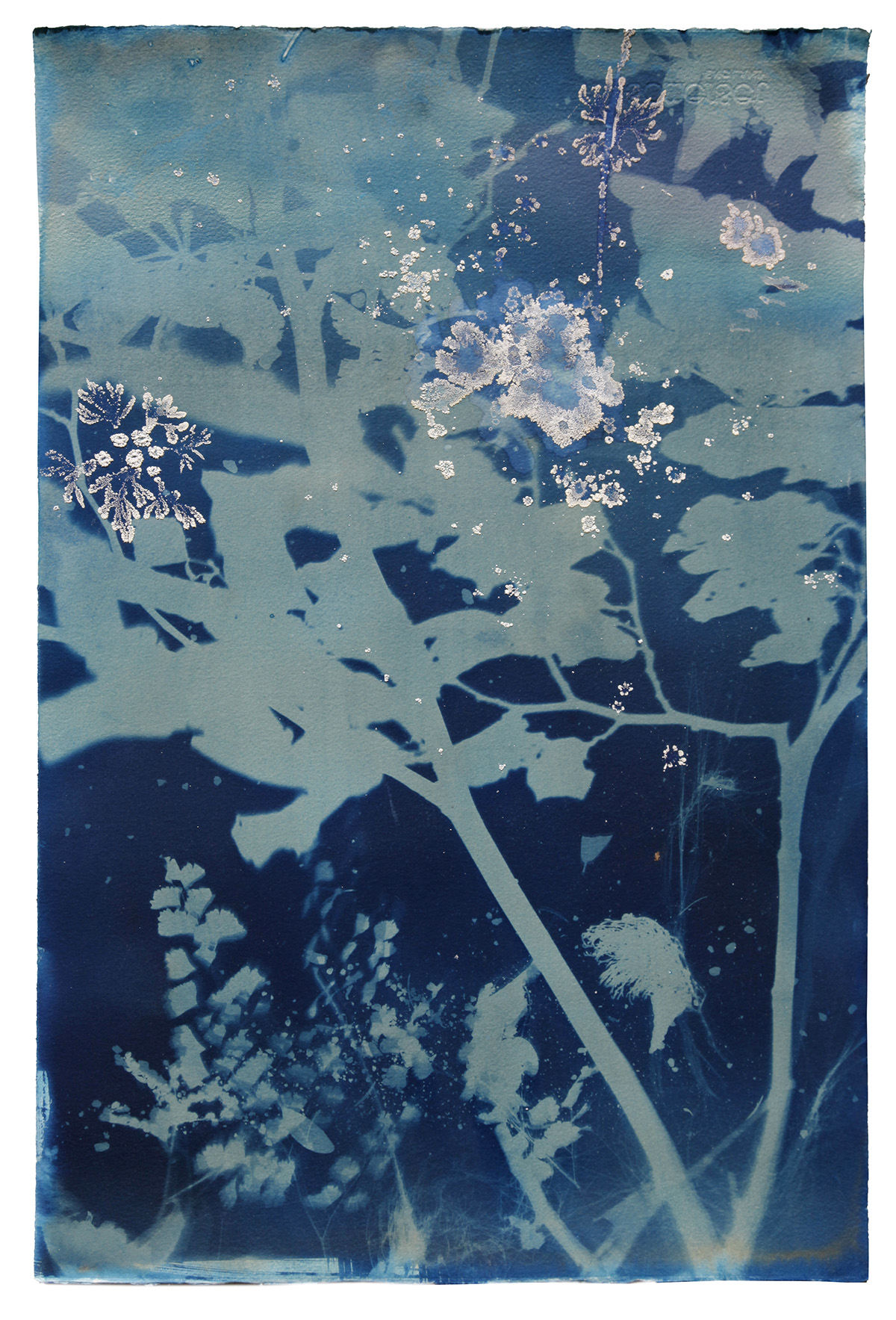

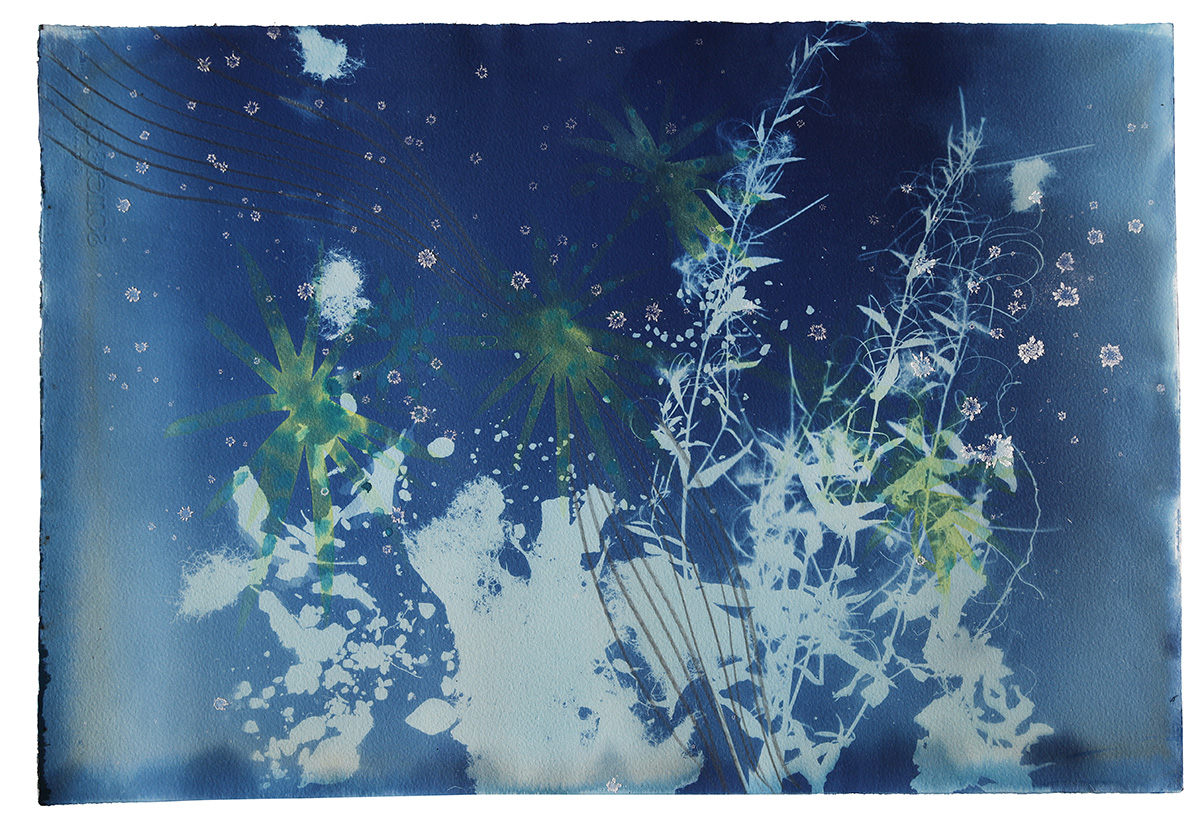

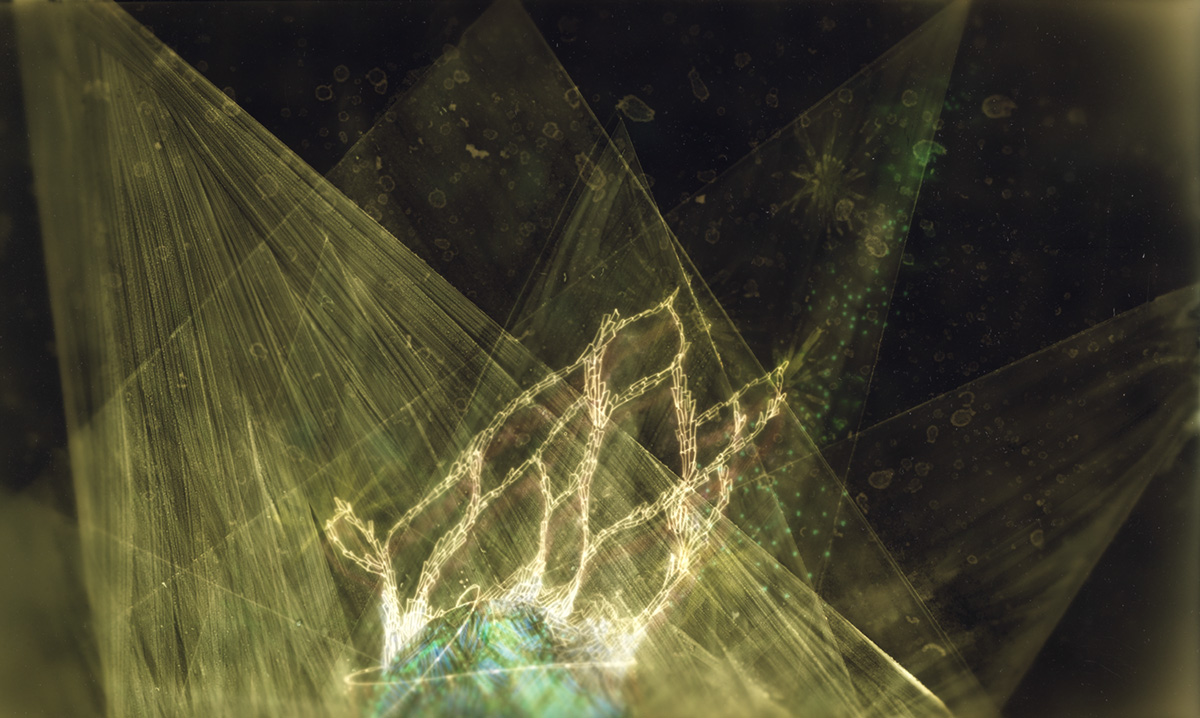

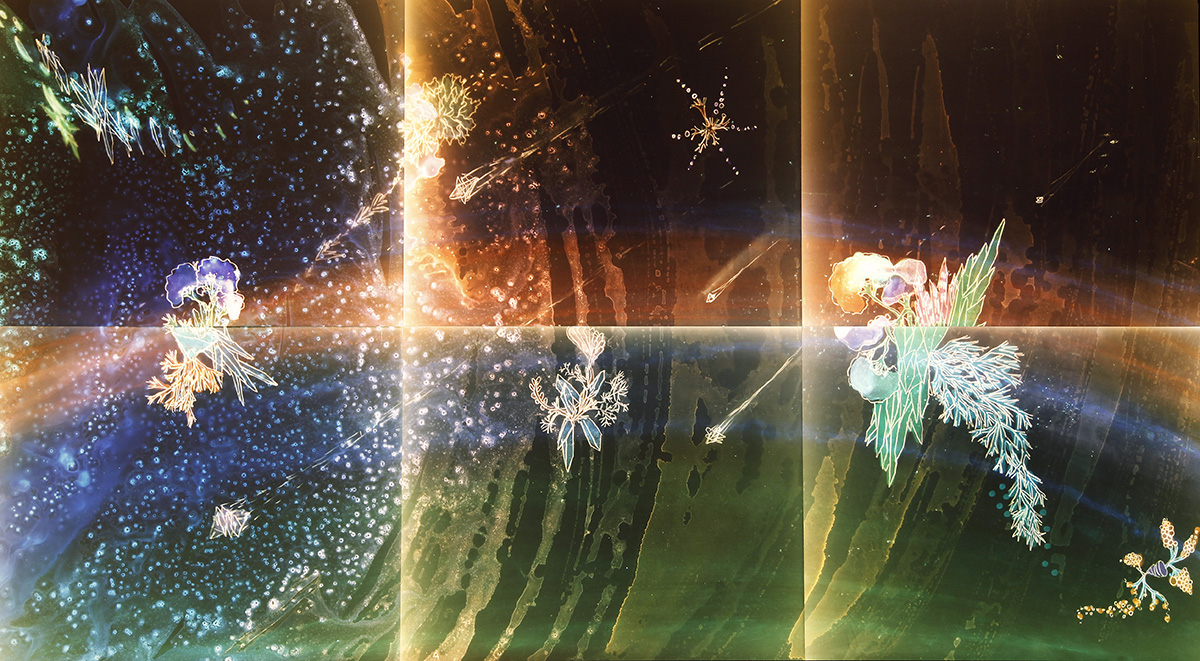

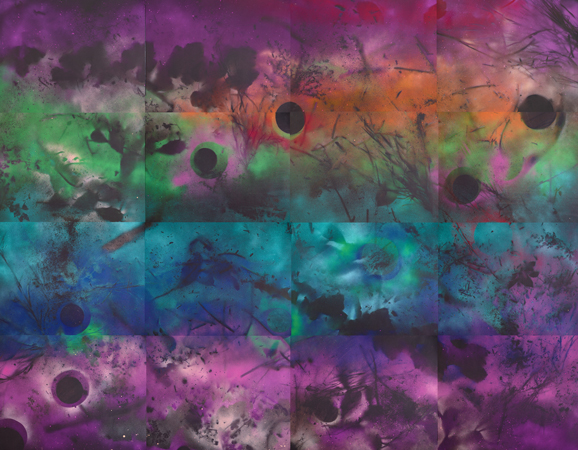

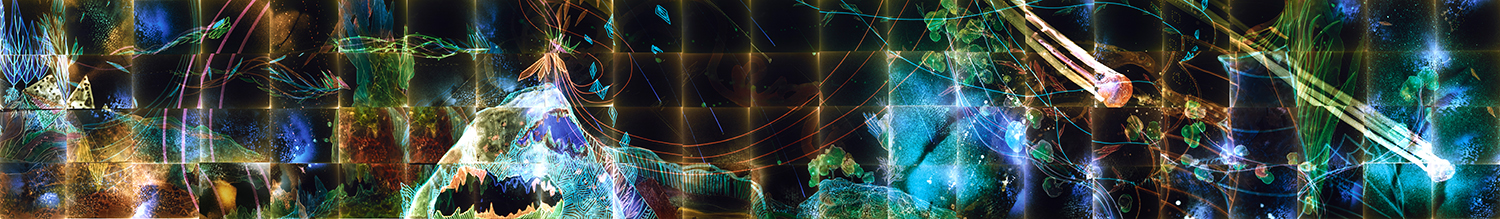

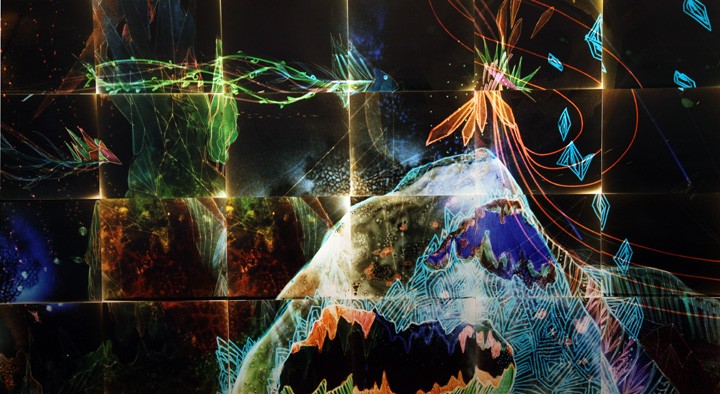

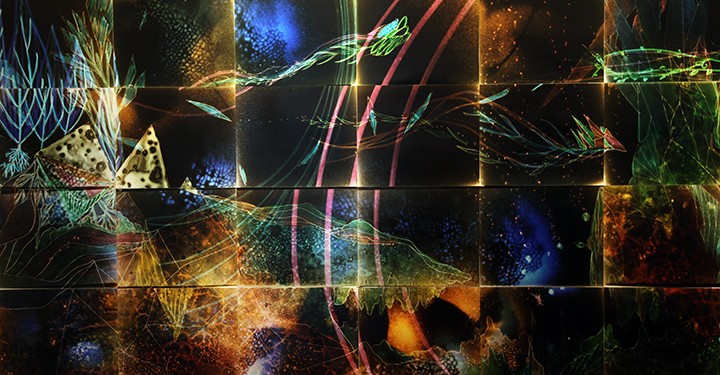

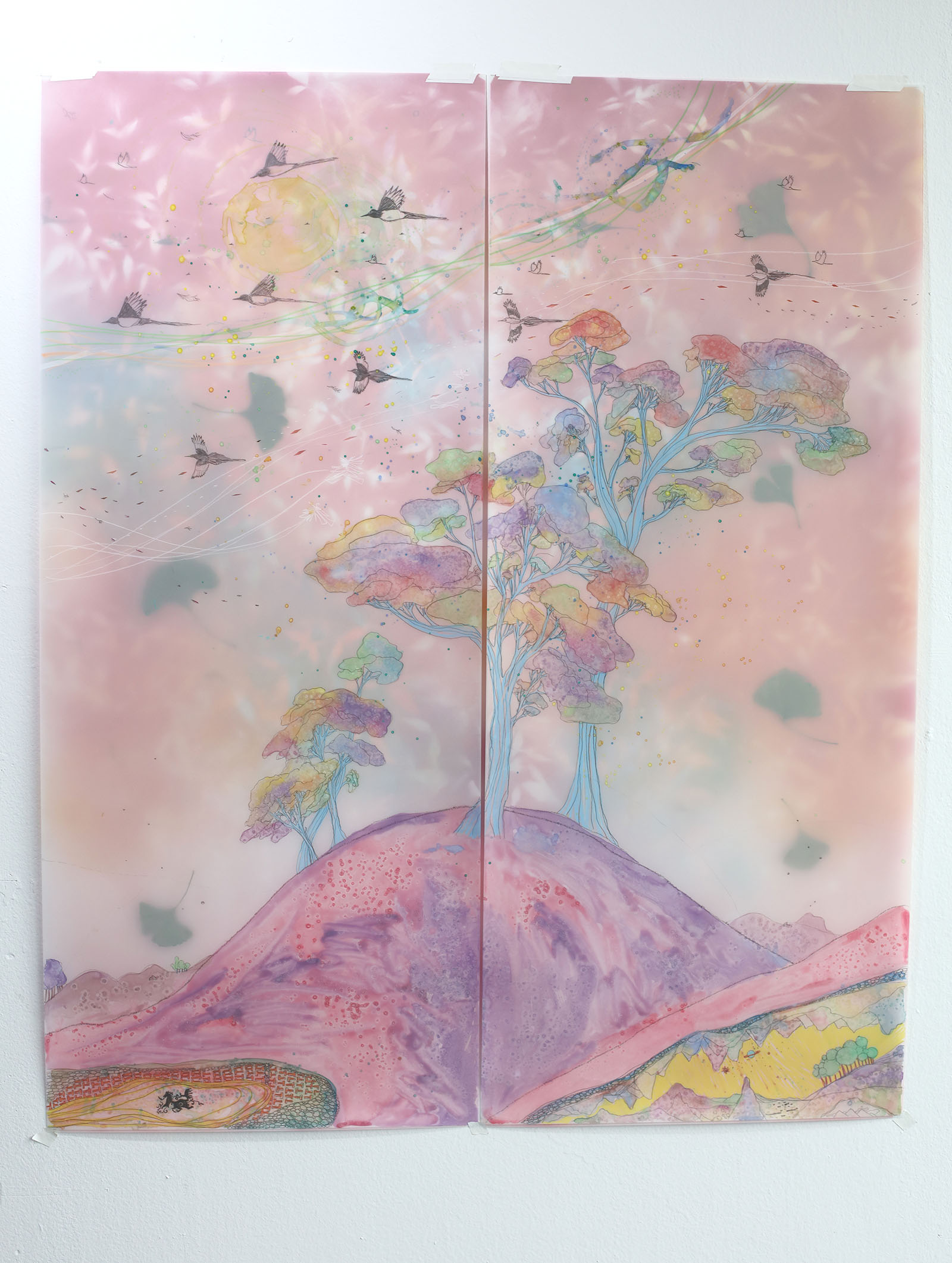

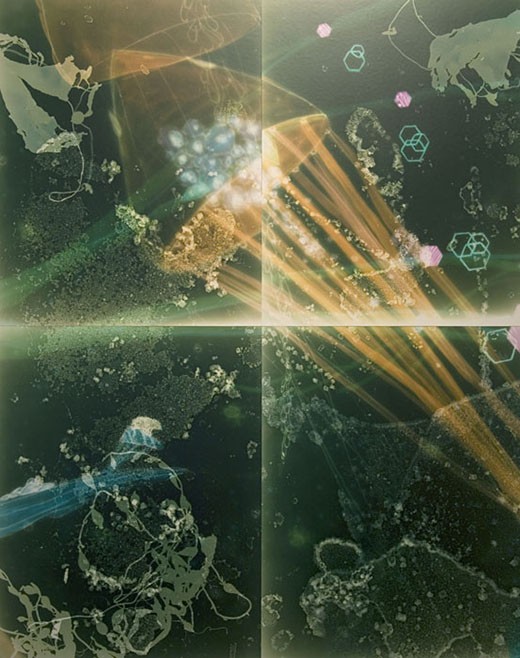

Early on, Nguyen established a way of working that had a connection to both drawing and photography. The continued use of this signature practice is evident in her exhibition Rock Paper Salt at the Huntington Beach Art Center. After drawings are made on sheets of translucent Mylar, several pages are sandwiched together and cut into sections. Each section with its layered stack of drawings becomes a photonegative. A color processor is then used to transmit light through the layered segments thus transferring a rendered impression onto photosensitive paper. Once the paper has been developed, all colors from the first drawings are seen in their complimentary hues (orange = blue, violet = yellow, et cetera) and reverse values (black = white for example). Finally, scores of the exposed sheets are rejoined edge-to-edge in a grid then mounted on a wall or portable foundation. This reconstruction, usually in a larger-scale picture, completes a single artwork.

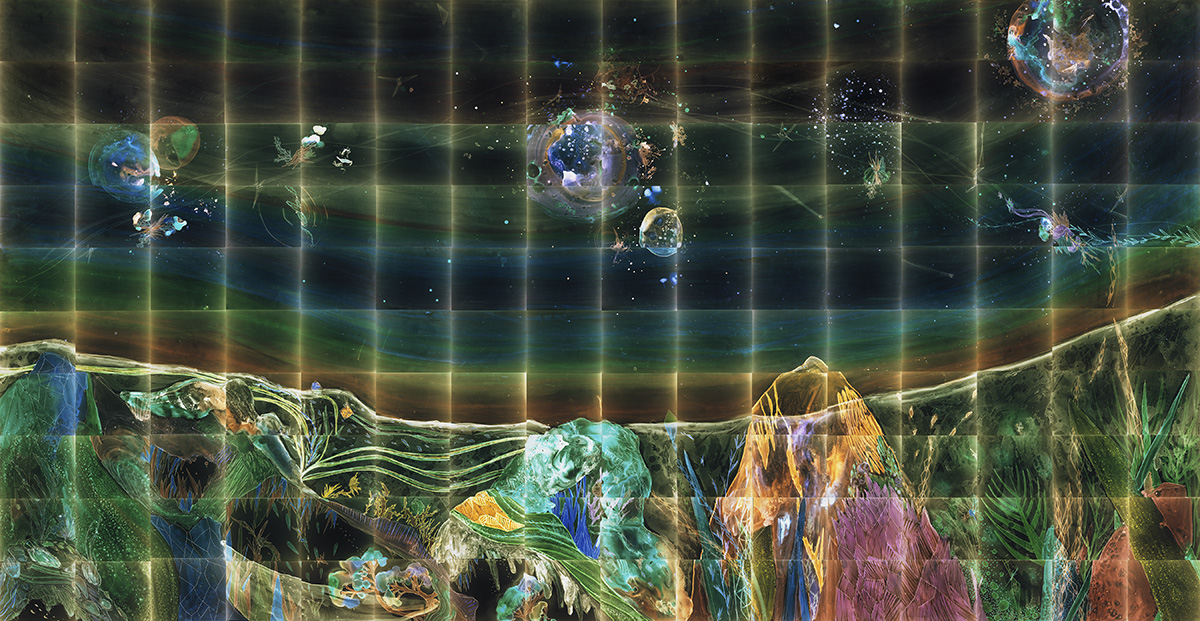

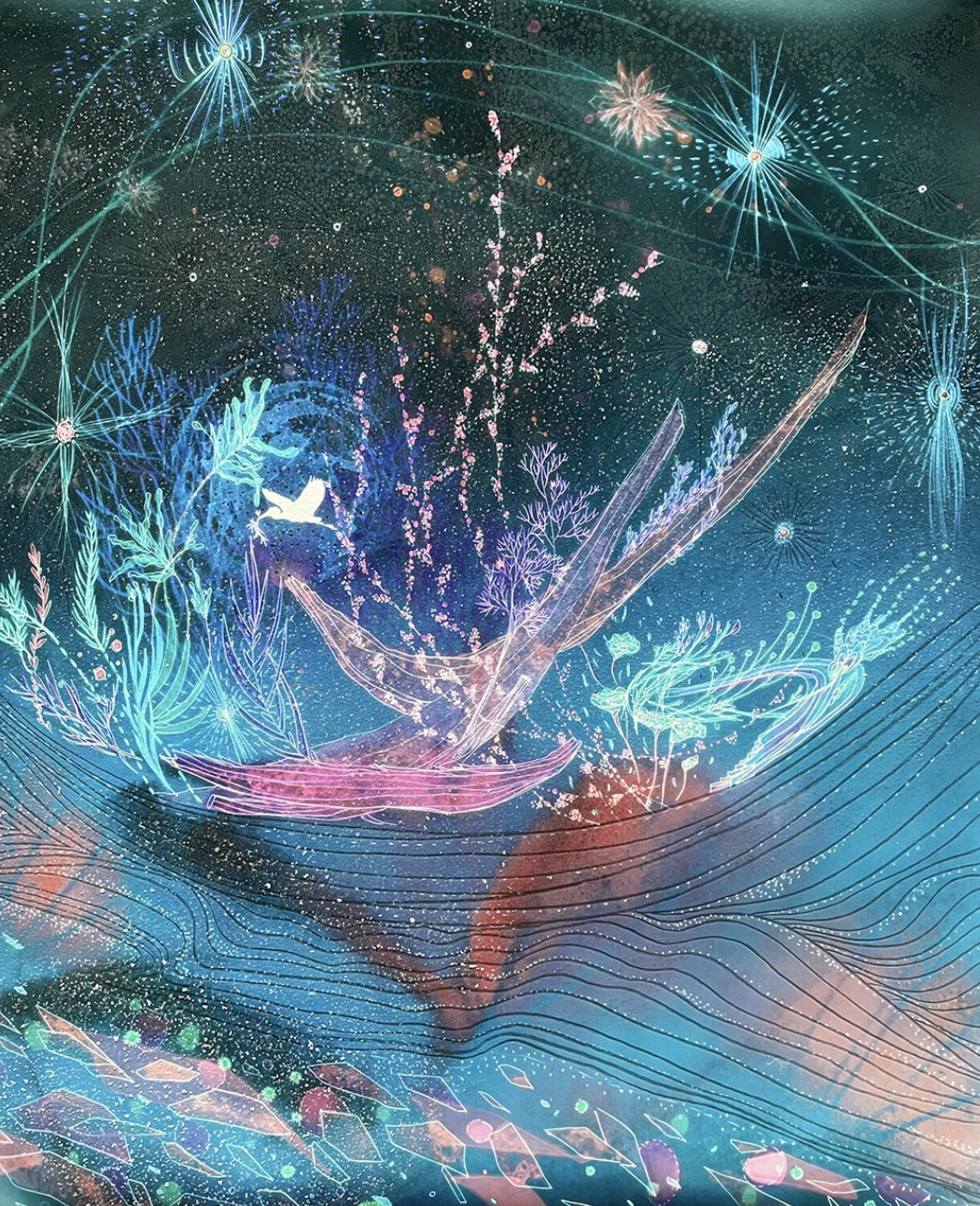

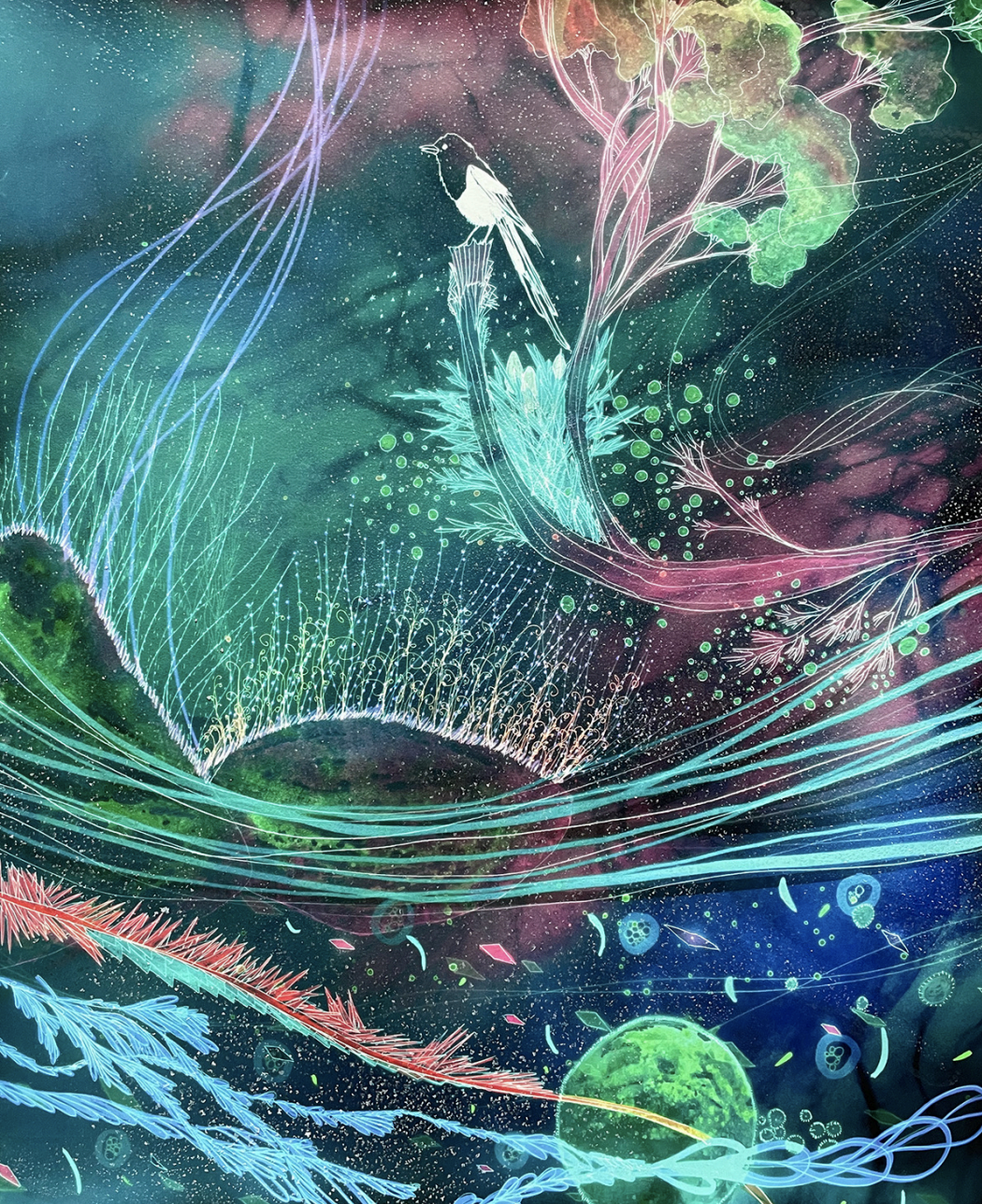

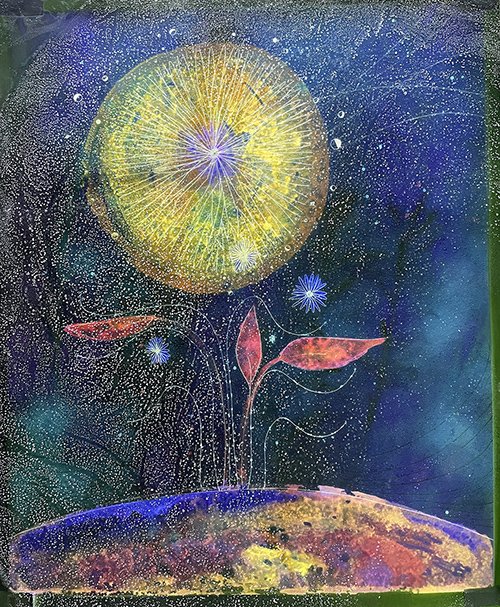

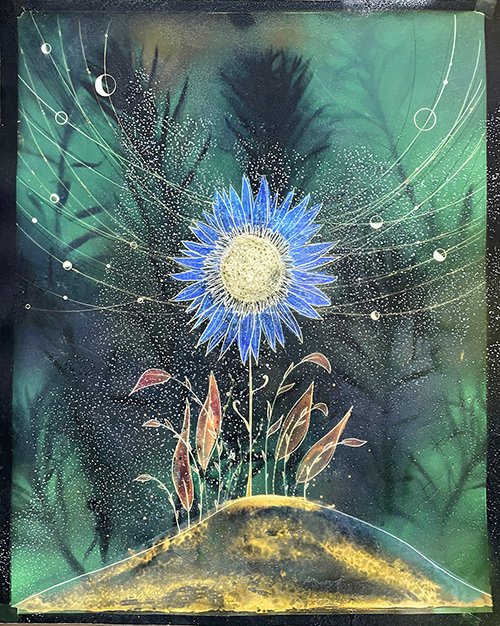

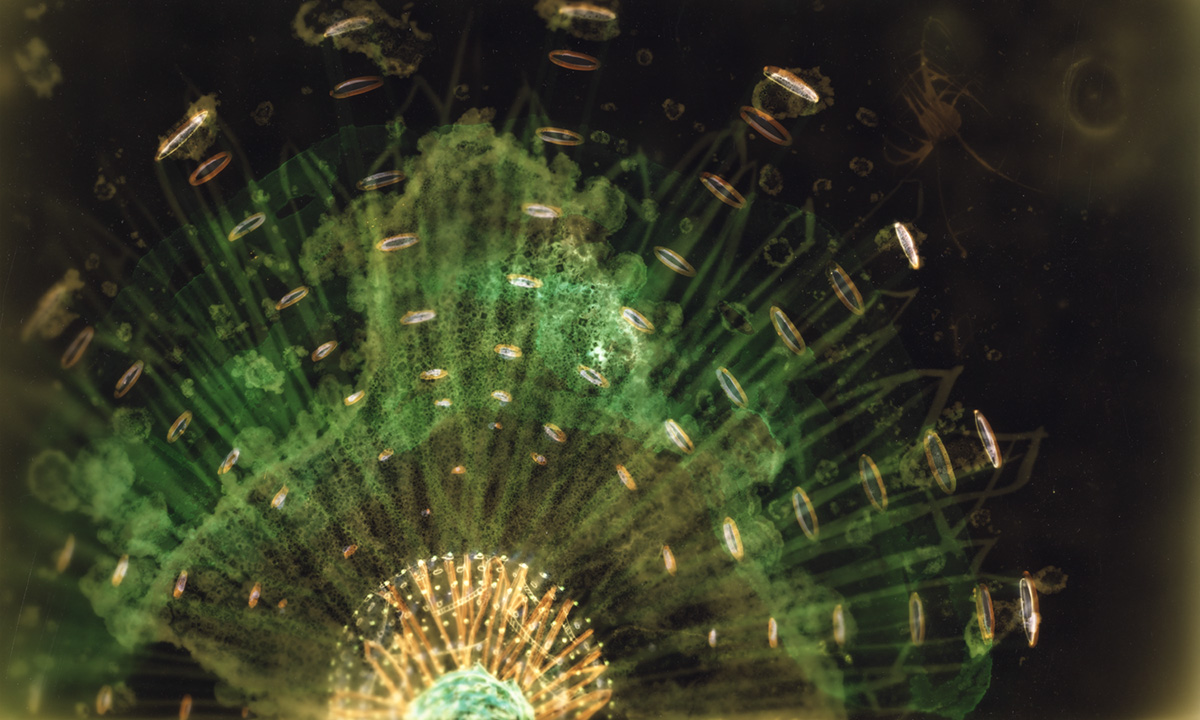

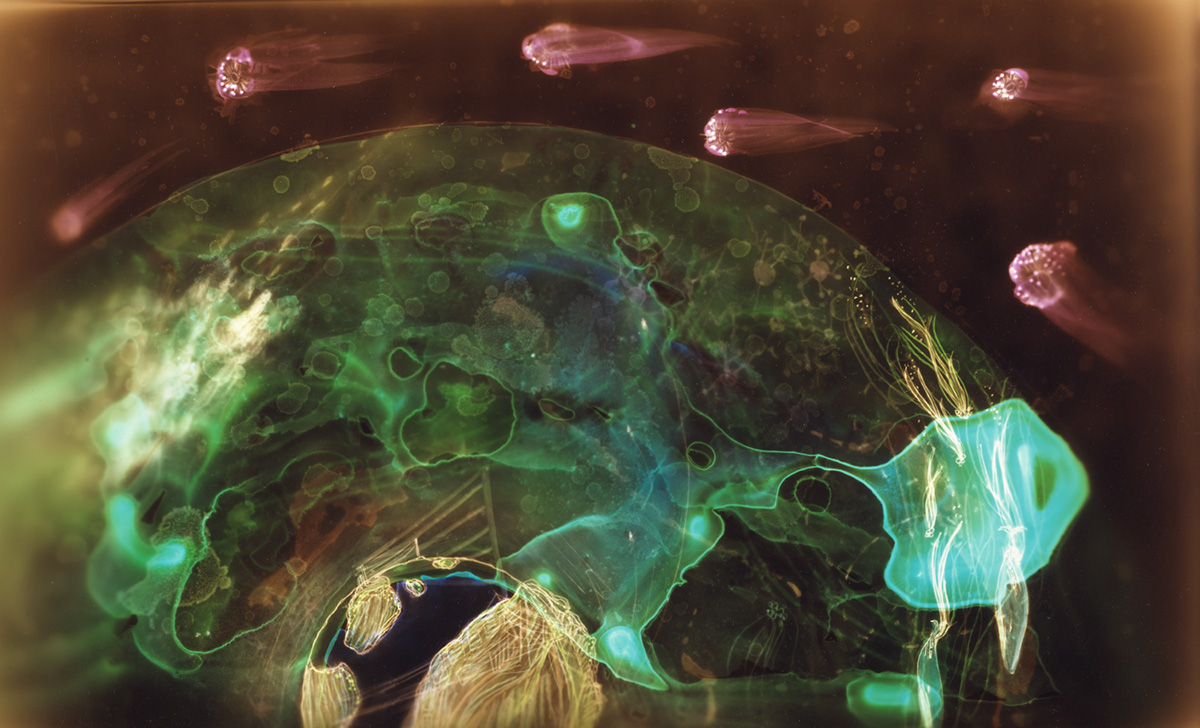

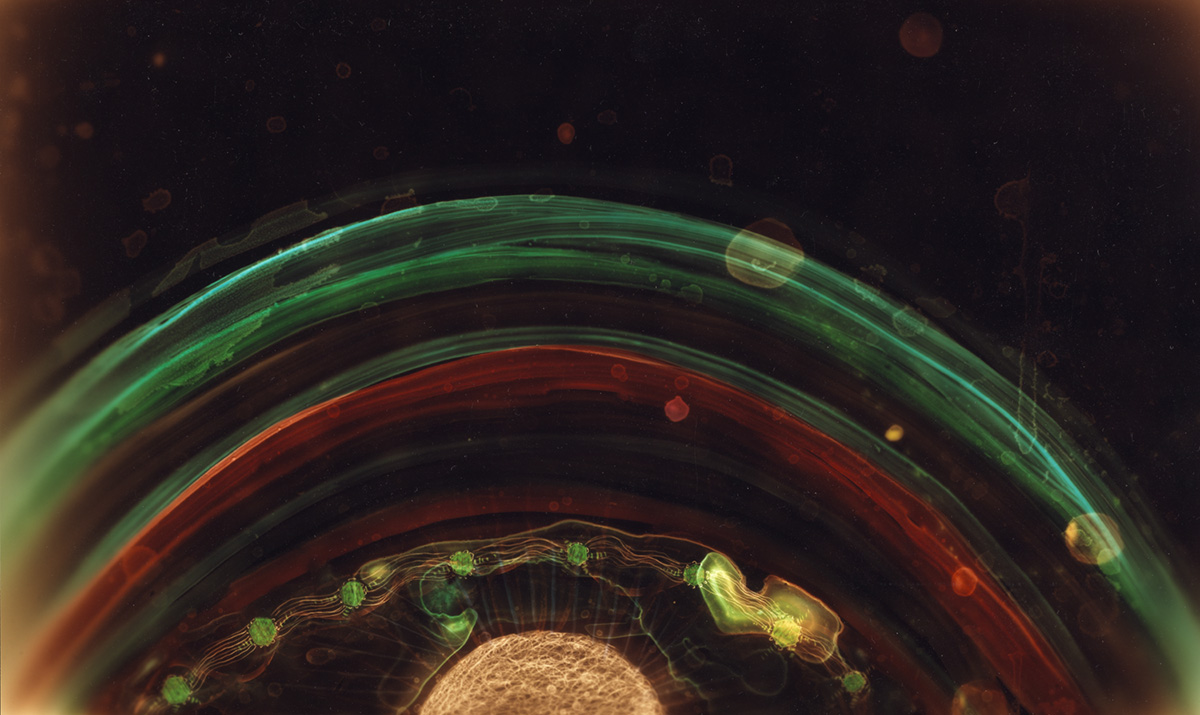

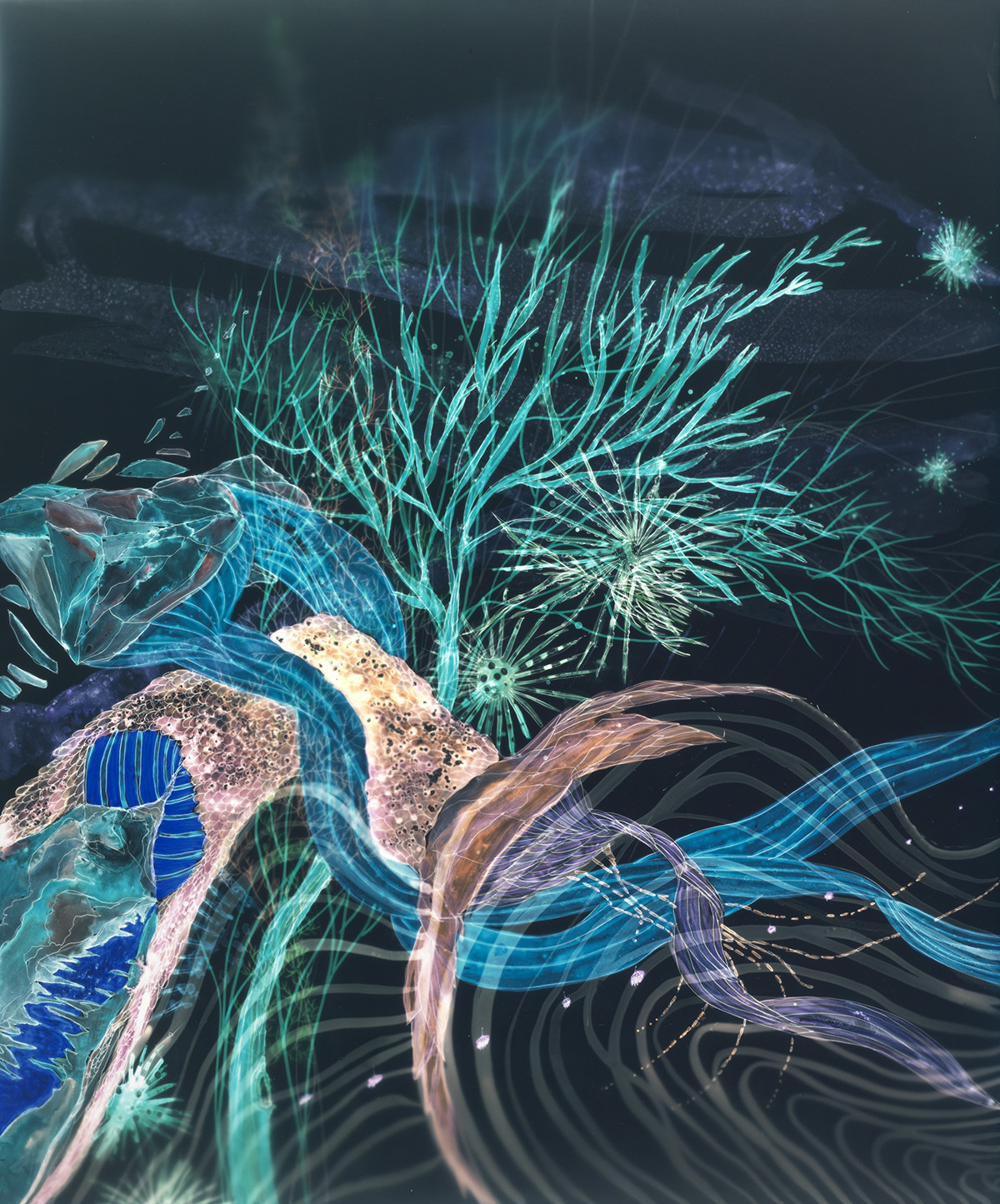

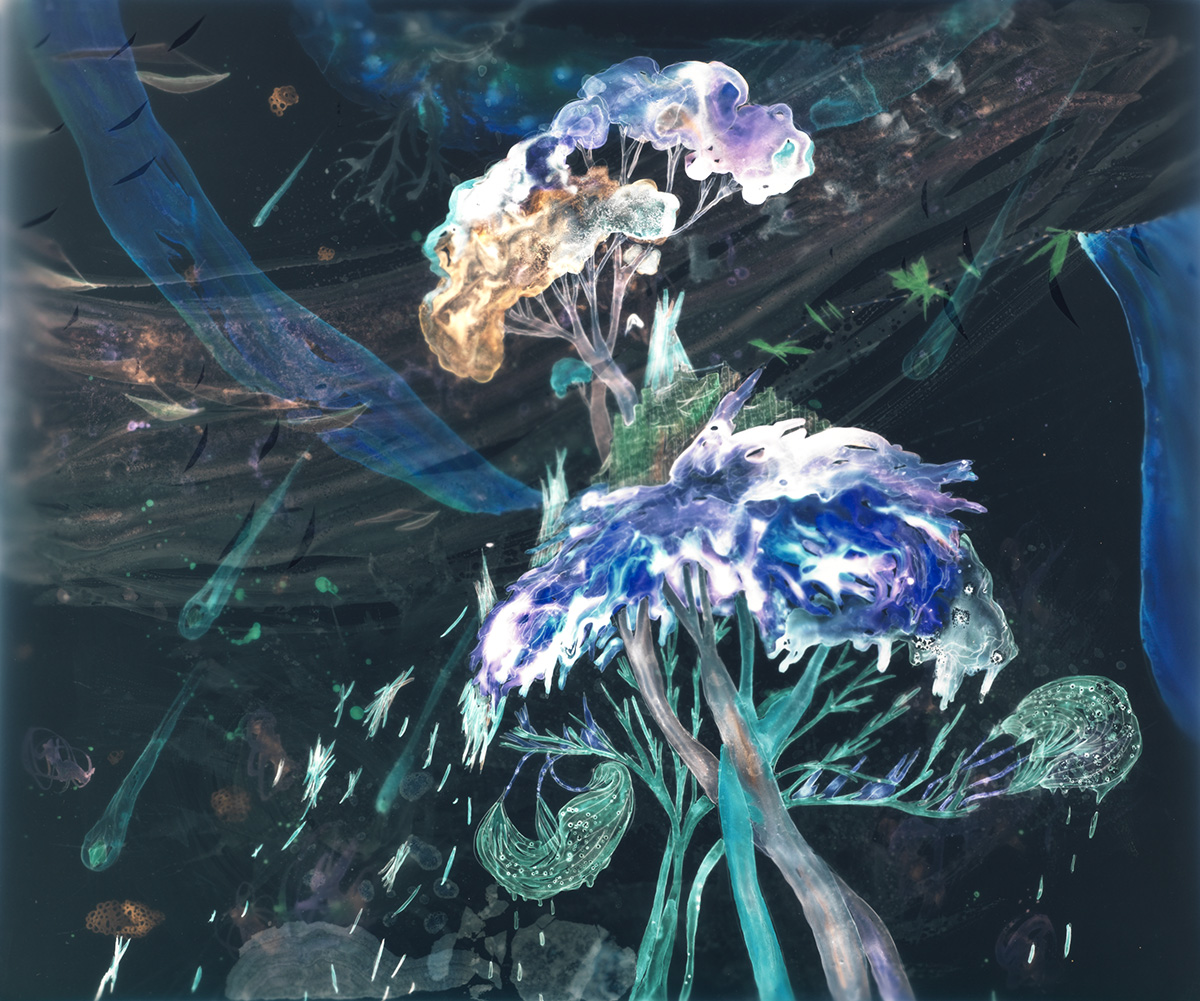

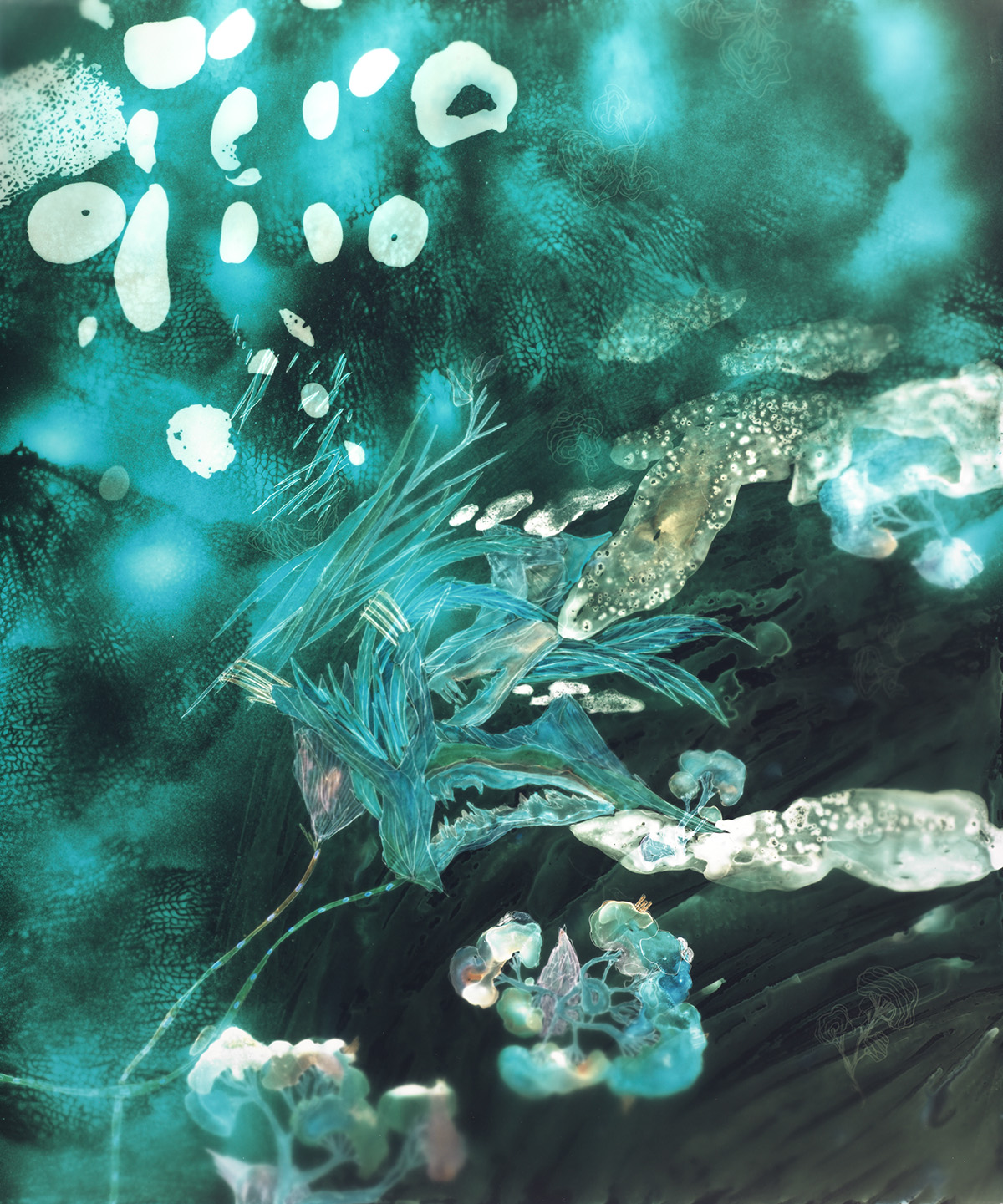

An excellent example of this type of work was shown during the last quarter of 2006 at UCLA’s Hammer Museum in Los Angeles. Nguyen unveiled a colossal three-wall photomural that depicted an underwater world where fantastic creatures live out their destinies. The extraordinary setting was like many of her smaller-scaled works that picture an array of delicate organisms, biologic elements, and crystalline particles floating in an uninterrupted sea-green space. These works speak of great bionetworks that exist outside the ecosphere of human discord. Multi-layered recyclable structures, hovering villages, spiny geologic minerals, thrashing primordial microbes, imaginary plants and a broad spectrum of jellylike apparitions are sprinkled like stardust throughout mysterious ethers, which appear to stretch from beyond earth’s permeable atmosphere to below its surface. Nguyen’s photomurals set a panorama of nebular space, slippery time, and infinite spectral light that can be equated with revelations perceived in the depths of slumber or through intergalactic travel. How did she arrive at such a far-reaching understanding of the world around her?

Nguyen’s father was a commercial fisherman who, for twenty years, fished off the coast of California from San Francisco to San Diego. While growing up she spent long hours visiting him on his boat. She helped with cleaning, painting, and sorting. After each eventful day that had been filled with new things to see and information to absorb, she observed him bringing all sorts of things in from the ocean. They were mysterious things saturated with the proof of their time underwater. One can imagine Nguyen as a child staring at the sea as if transported into a distant world. She must have awakened to a new way of thinking — a universe teeming with visual imagery and possibility.

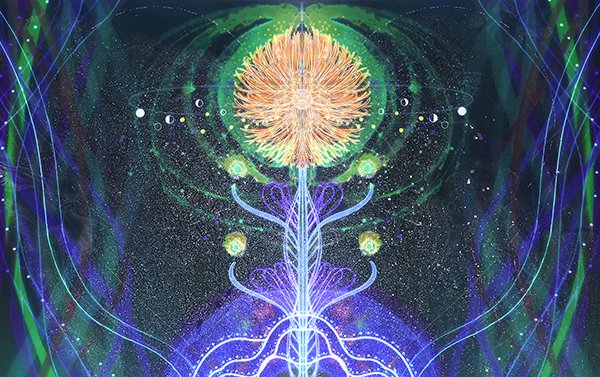

This place emanates from a point we may never fully understand. It can be found poised at the twilight of a lucid dream, indistinguishable from spiritual meditations that beg us to surrender all things to exclusion of one. Only Nguyen’s world of deep liquidy space is filled with curious bits and pieces, glowing plants, cityscapes, machines, and illuminated creatures. It is an ecotopia caught at an intersection of time. A vista is at all times present but always changing. Mental pictures quietly drift in darkness shuffling their perspectives from top view to side view, only to roll back again to three-quarter position. Nguyen has tapped into this location where all things seem to radiate from unidentified sources. And even though she does not fully disconnect from utopian-inspired tales or from the simulacra we encounter each day, what makes her work unique is its enduring vision, its completed form of storytelling. And the telling is what makes it extraordinary. It most likely contained seawater.

Encircled by strange ethereal space, Nguyen’s imaginary beings exist in symbiotic harmony. Different species rally around each other in associations that are mutually beneficial. The artist’s system for generating such behavior in her characters is always mindful of nature’s sometimes imperceptible order. Long before the hammer Museum show, she had produced a glossary with names for each of her make-believe creatures and the places they occupy. The natural relationships of diverse organisms existing within an ordered system were defined, and combinations of words identified their earthlier activities and unspoken contracts. A Transient Botanical City, for example, is composed of botanical wires, bulb houses, and seedlings of Pod Angels. Tunnels for transportation and waste disposal systems are connected to it, thereby offering the city as an ecologically safe zone. Pod Angels grow on the wires of botanical cities. They absorb energy from the city and fly away when they reach maturity. Others like the Owlchiyu only hatch once every twenty-three years. After hatching it has three days to cure beings in need (its feathers are made up of various types of healing vegetation). Lamenting Orbals swim around collecting sadness and negative emotions from others. To do this they stare into the other’s eyes or kiss them to absorb the tears. The planet-shaped Orbals have a mission, and their spherical nature serves as a ground for self discovery and the circulation of experiences that are accessible to everyone. They are spared the indignities of living a more human kind of existence that is rife with ambition, self-flattery, prejudice, and other societal hostilities instigated by fierce individualists or multinational predators that prey upon citizens. Still, everything seems reasonable and the fantasy plausible.

Nguyen’s make-belief creatures always have a reason for being and a persistent purpose. They are not designed to squelch the competition or excrete violence against the natural world. They serve out their short lifespans on an Oatmeal Island or in a Parable Echoes Tower like divine spirits spiraling inside a grand hallucination. All things are in agreement. Each relationship is loaded with social equality. A sense of synchronization, balance, and steadiness is maintained. Nguyen, an observer of human experience, is able to sustain the illusion of tranquility she presents to the viewer, because her vision of conceptual emancipation is one that parallels the sincere human desire to seek and struggle for both individual and collective happiness. It is, however, in conflict with the equally human aim to compete, even destroy or kill for survival. The tight spot — to desire freedom from rivalry on the one hand, while actively striving to prevail on the other — is mutely subtracted from Nguyen’s imaginary social system. The fictional territories, idiosyncratic personalities, and immaculate events represented in her work always veer far from earthly ones that are routinely weighed down by an unrelenting awkwardness. Perhaps her contribution is to articulate our yearning for a better world and to make her objectives distinguishable from gloomier proposals that encourage hopelessness. It takes some suspension of disbelief. The reality is that we need Nguyen’s art in our world now more than ever.

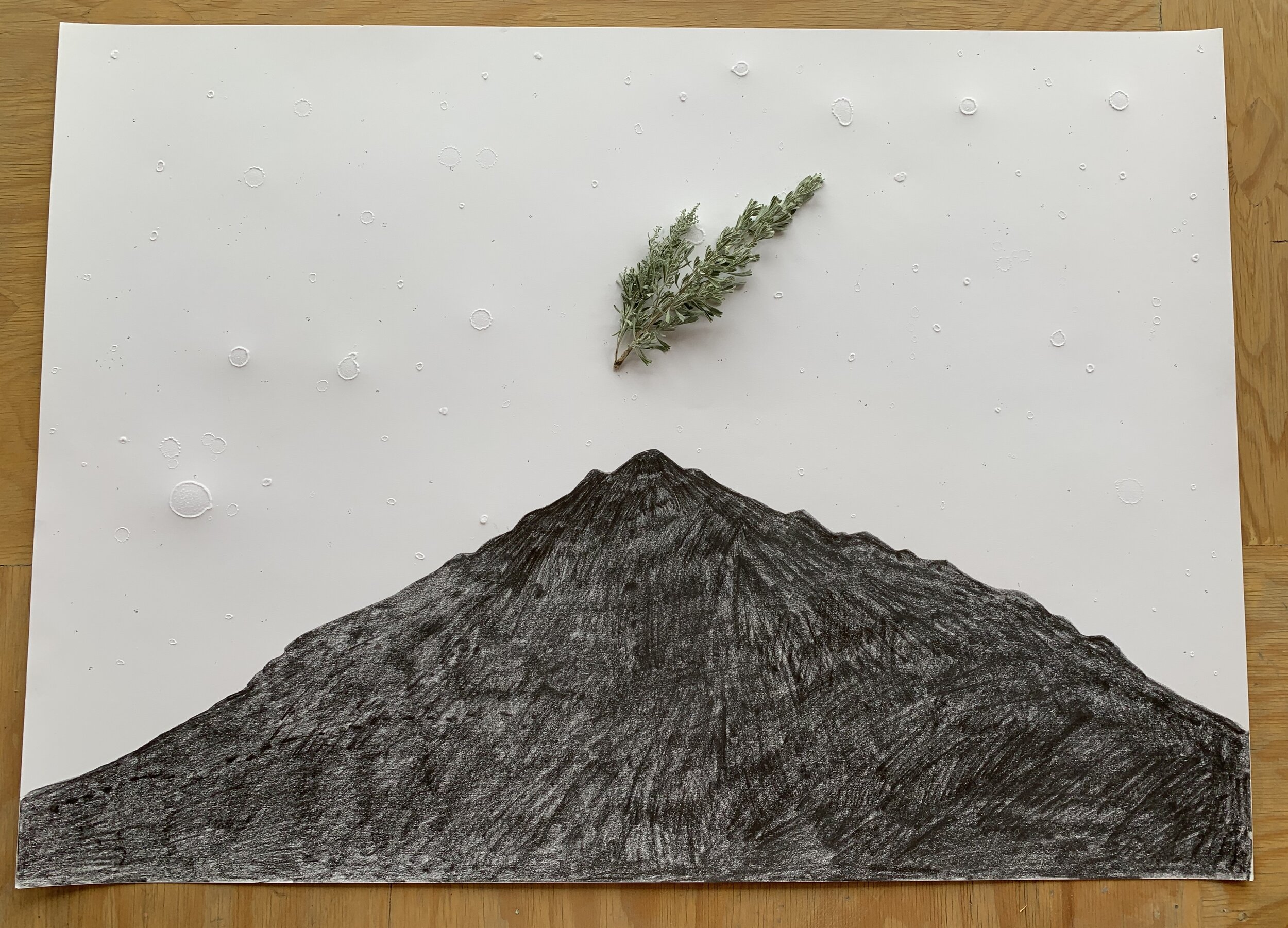

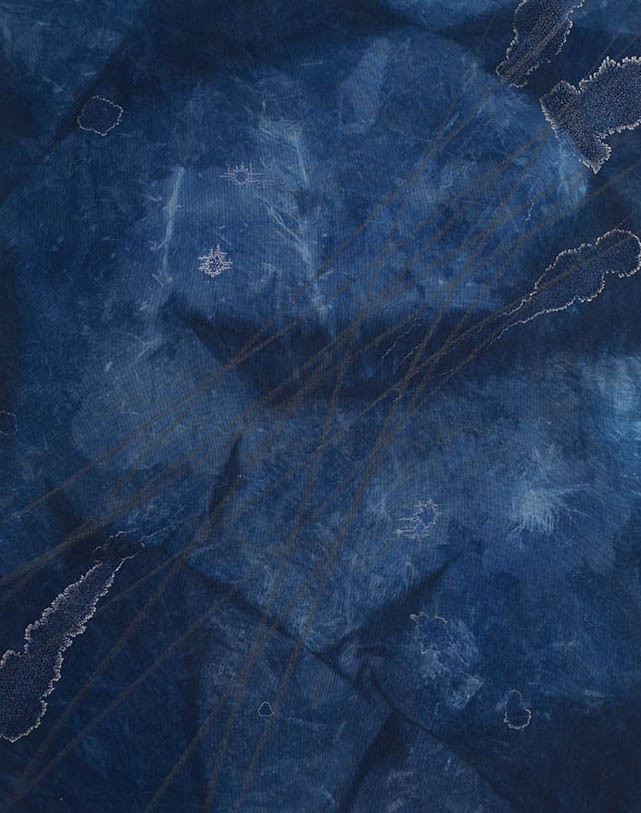

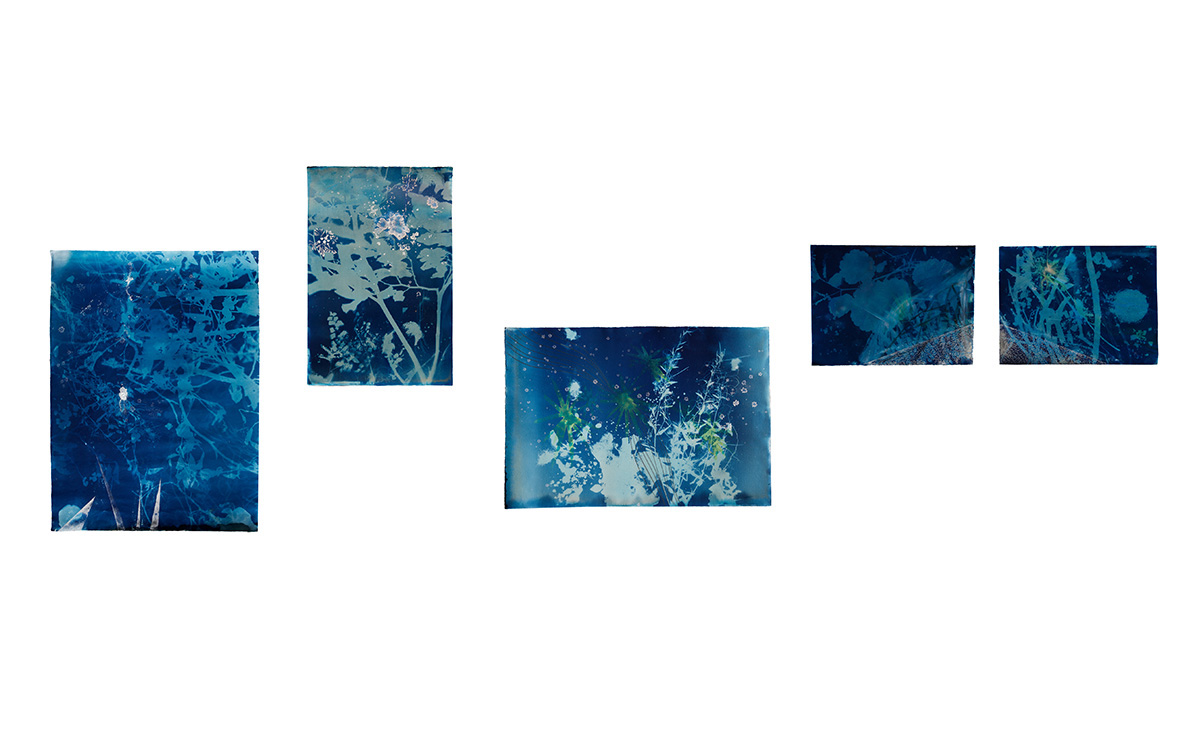

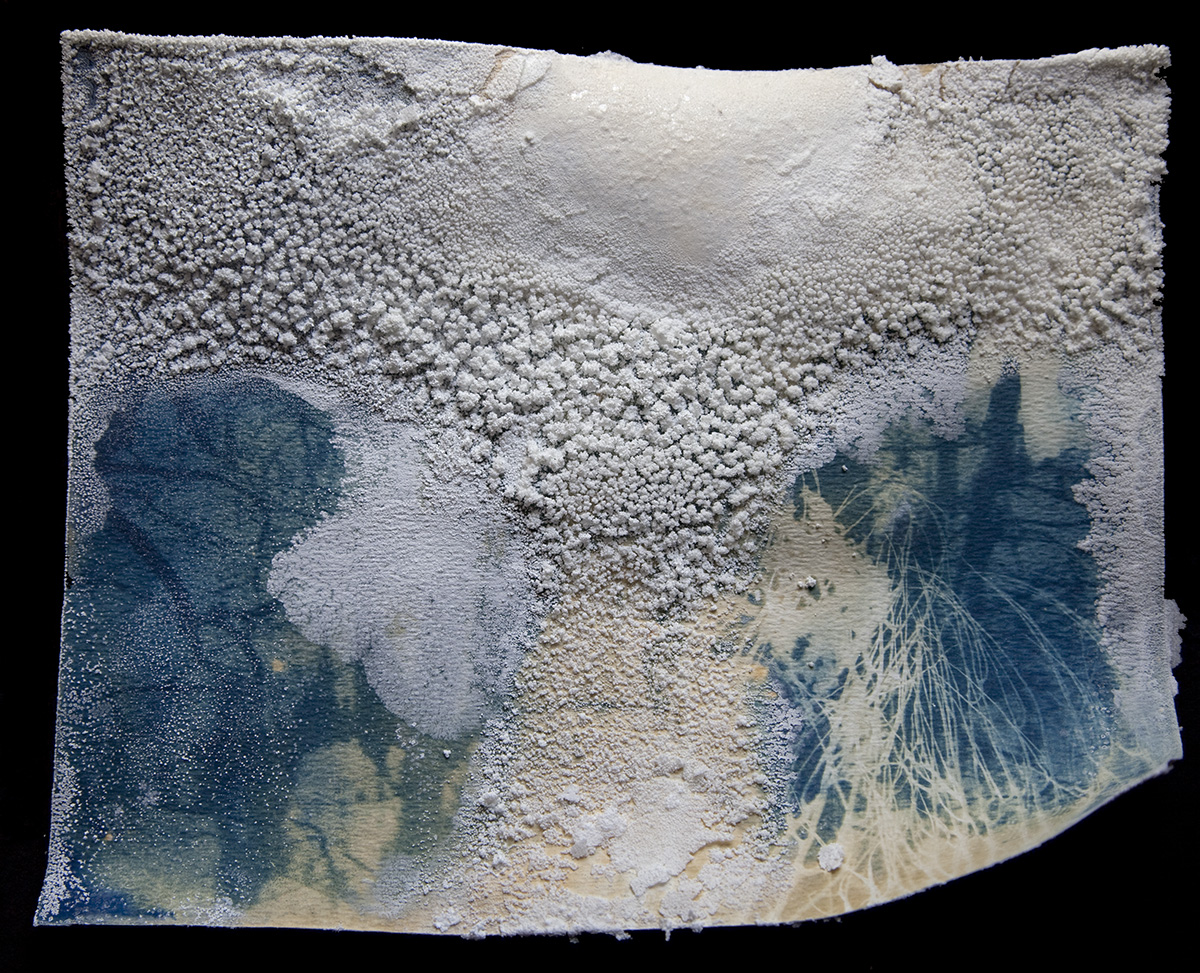

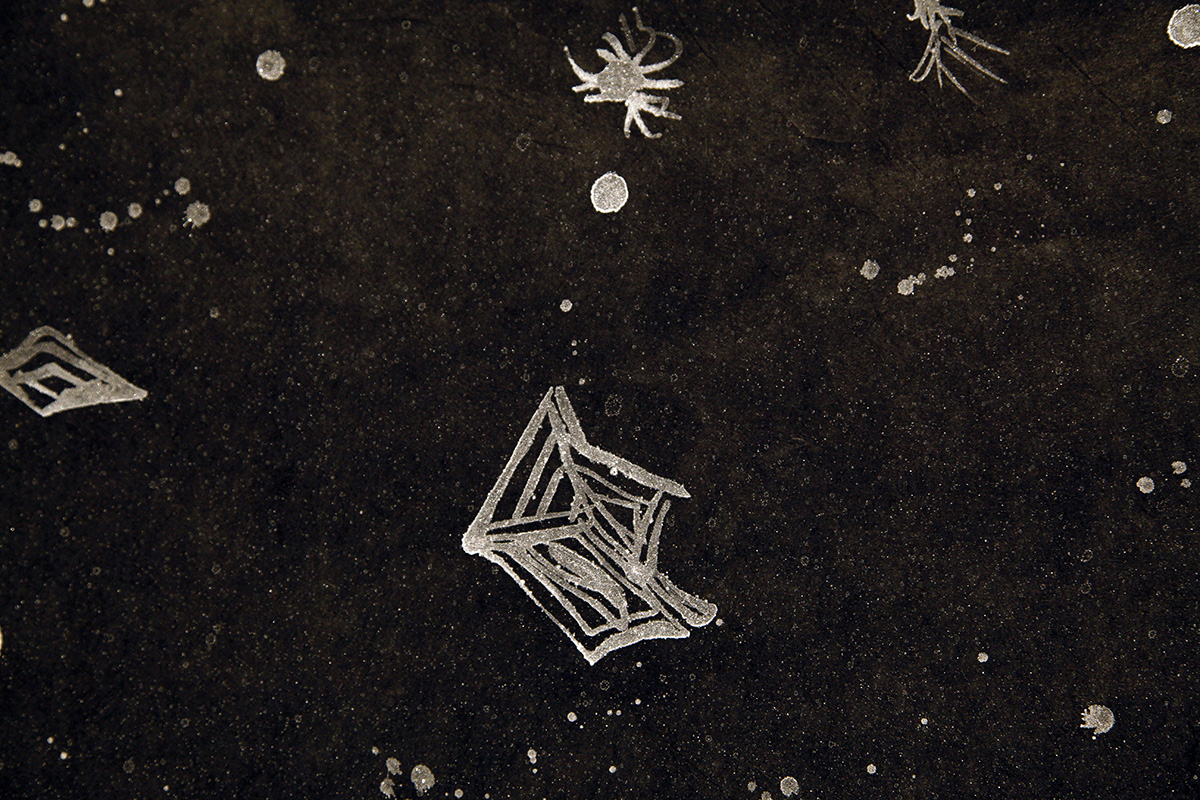

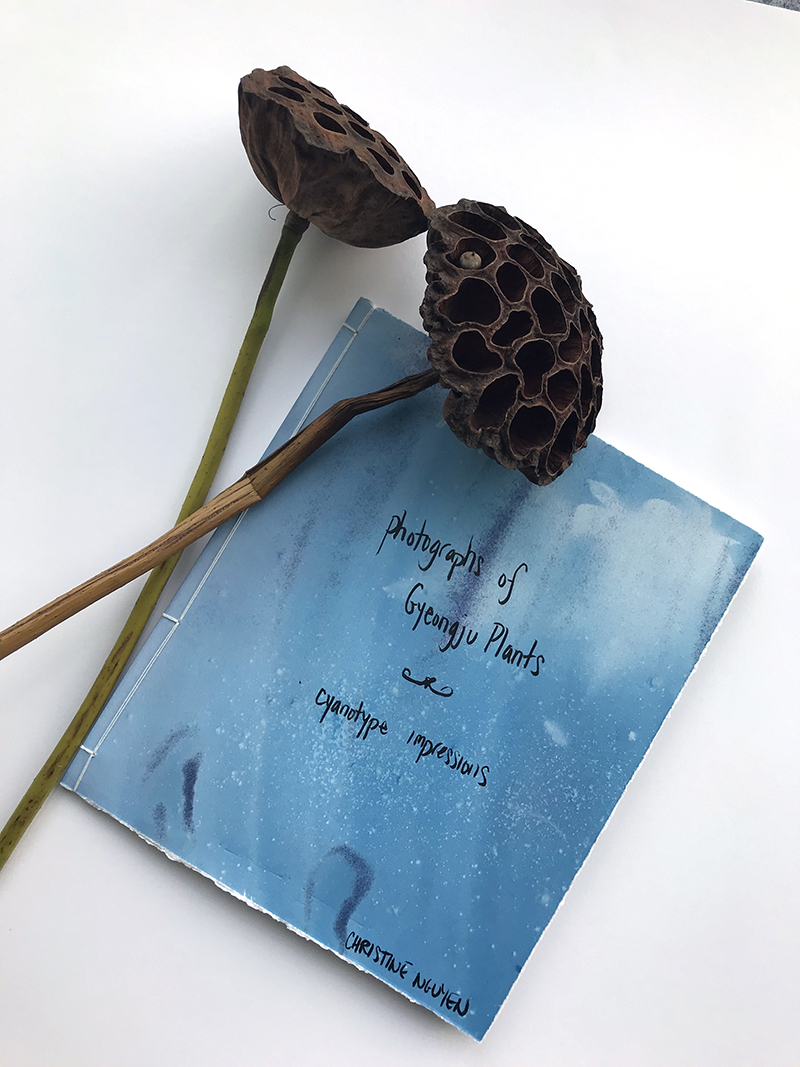

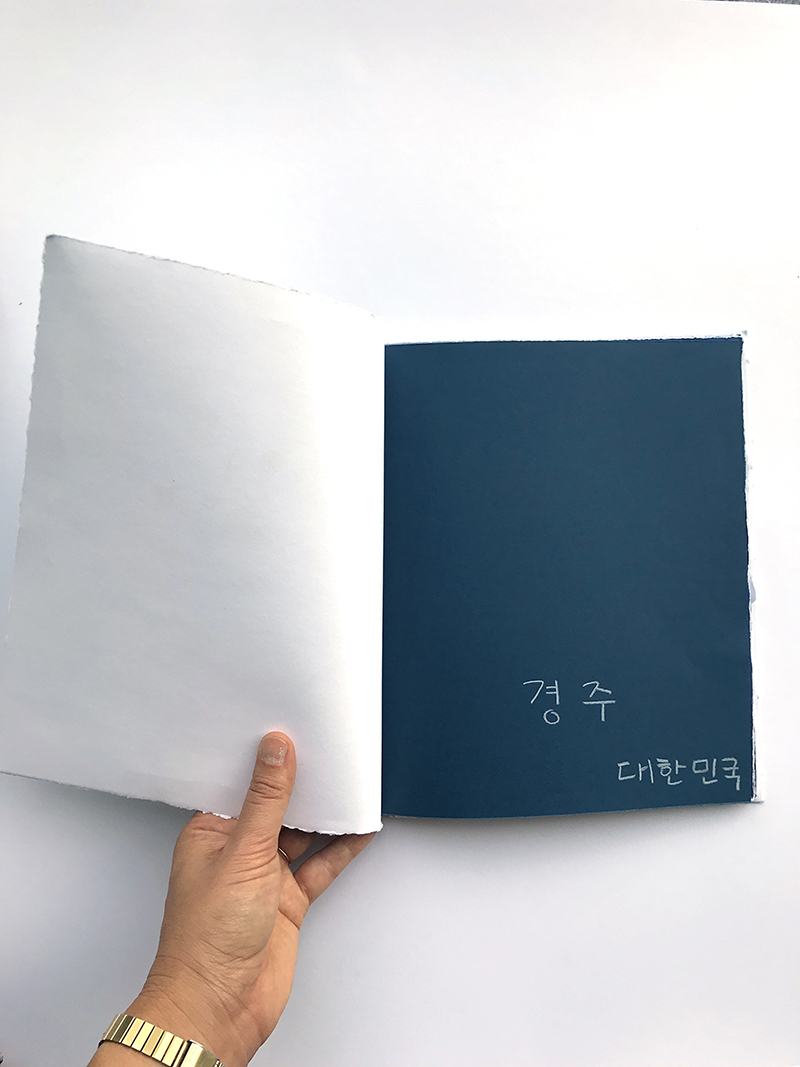

In October of 2008, during her one-month residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin County, Nguyen explored the immediate landscape along the California coastline that neighbors the city of San Francisco. Located a few miles north across the Golden Gate Bridge, “There were hiking trails everywhere filled with wildlife and nature,” Nguyen said later. On her walks she collected sea plants, shells, coral, and multi-colored pebbles while photographing the surrounding landscapes. Then, after returning to her Headlands studio she processed the snapshots and went on to grow salt crystals on the prints and on some of the other things she had found.

There are two ways Nguyen learned how to grow salt crystals on various surfaces. One is an evaporation method where she places an object in a tray, fills the tray with water, and lets it swiftly and naturally evaporate. As the moisture vanishes, salt crystals form around the object. Another procedure is to place the object in a jar, and fill it with a super-saturated saltwater solution. In this case, the solution is kept moist with no allowance for evaporation. Slowly cubic salt crystals will grow, but it takes days, sometimes weeks depending on the available temperature and humidity.

The crystals give her photographs an added dimension of reality. Glistening prints of sea cliffs at foggy shoreline points, big ocean rocks, and beautiful clinging crustaceans along the coast are powerful notes to a viewer’s subconscious mind. The general message is that untainted marine scents and ocean sounds have been squeezed out of our inborn sense receptors. Even if we live near the ocean, our contact with it is now being simulated via electronic data and Internet searches for old Jaws 3-D t-shirts and matching beach towels. Nguyen distances her work from the alluring sparkle of cyberspace that always seems to tug for our attention. Her snapshots become tangible warning signs existing to inform us that the loss of all things natural has been prearranged. It is probably not all bad but maybe a little troubling that for many of us today, a trip to a seaside resort hotel or nearby maritime museum and aquarium is equivalent to “ocean experience.” We have lost our way, and Nguyen’s art is the tip-off that a digitally enhanced Jacques-Yves Cousteau television film special on marine mammals is, perhaps, the closest thing we have to the natural briny scents and soothing bubbly sounds of the deep sea.

Maybe we need less analysis. The content of Christine Nguyen’s work relies more on her desire to understand and communicate ideas that were set in motion when she was younger than it depends on art or theoretical references. Her galaxy of all-encompassing vistas, meandering waterways beneath oceans, swarms of color that look like pools of light all come from her early experiences and from the memory of those experiences. The delicate life forms and strange miniscule sea creatures that at times seem alien and abstracted when viewing her work are part of that memory but also part of Nguyen’s mature comprehension and appreciation of idiosyncratic characters and idealized locales. A blurb of color that first emerges as a community of fish underwater may gradually morph into a beautifully configured pattern. A cross-stitch of light on photo paper is not simply an intersection, but a portal to another condition floating between circumstances — a threshold, which stands between one earth and another or the end of one idea and the start of a new one that is still connected to ancient seas and space.

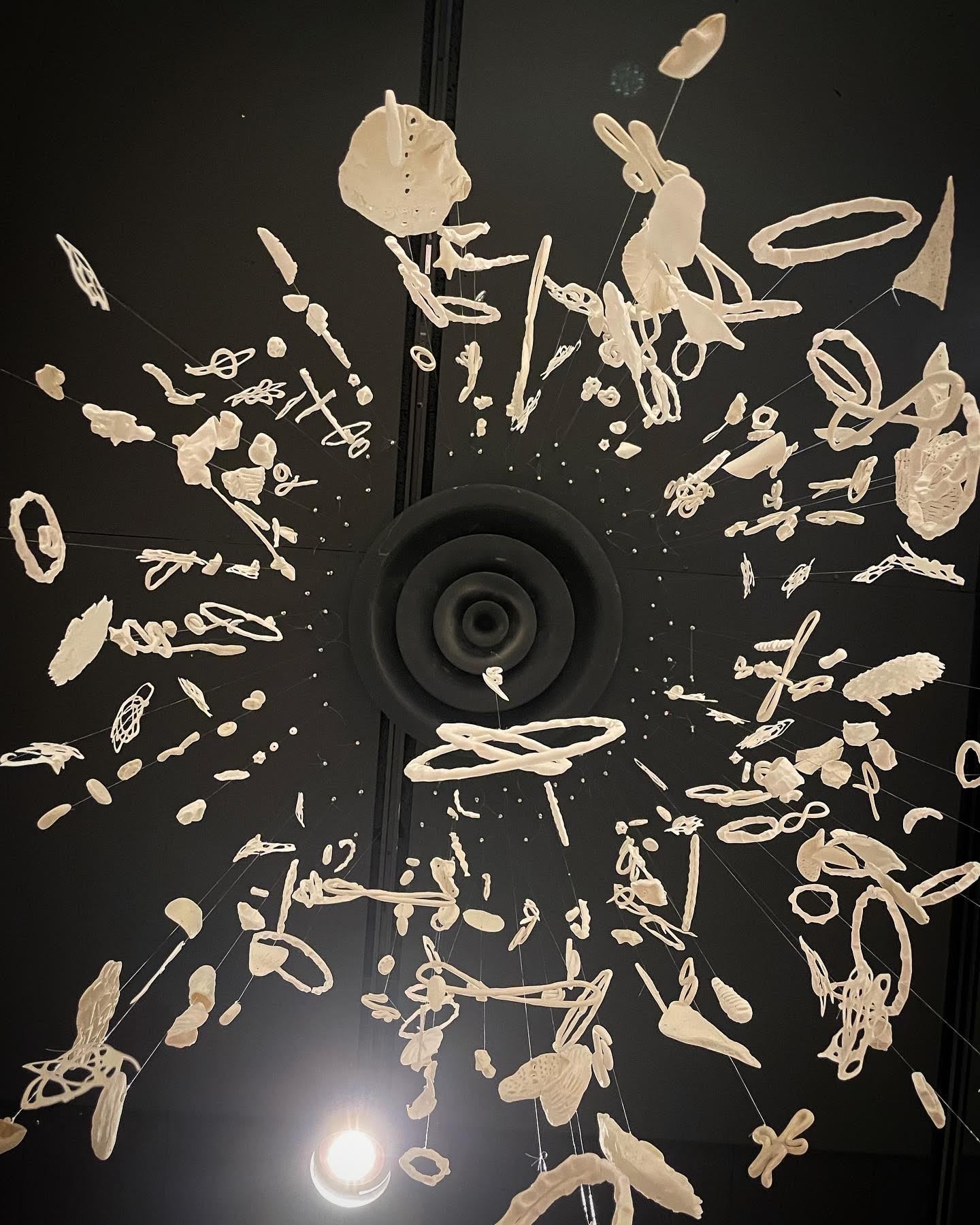

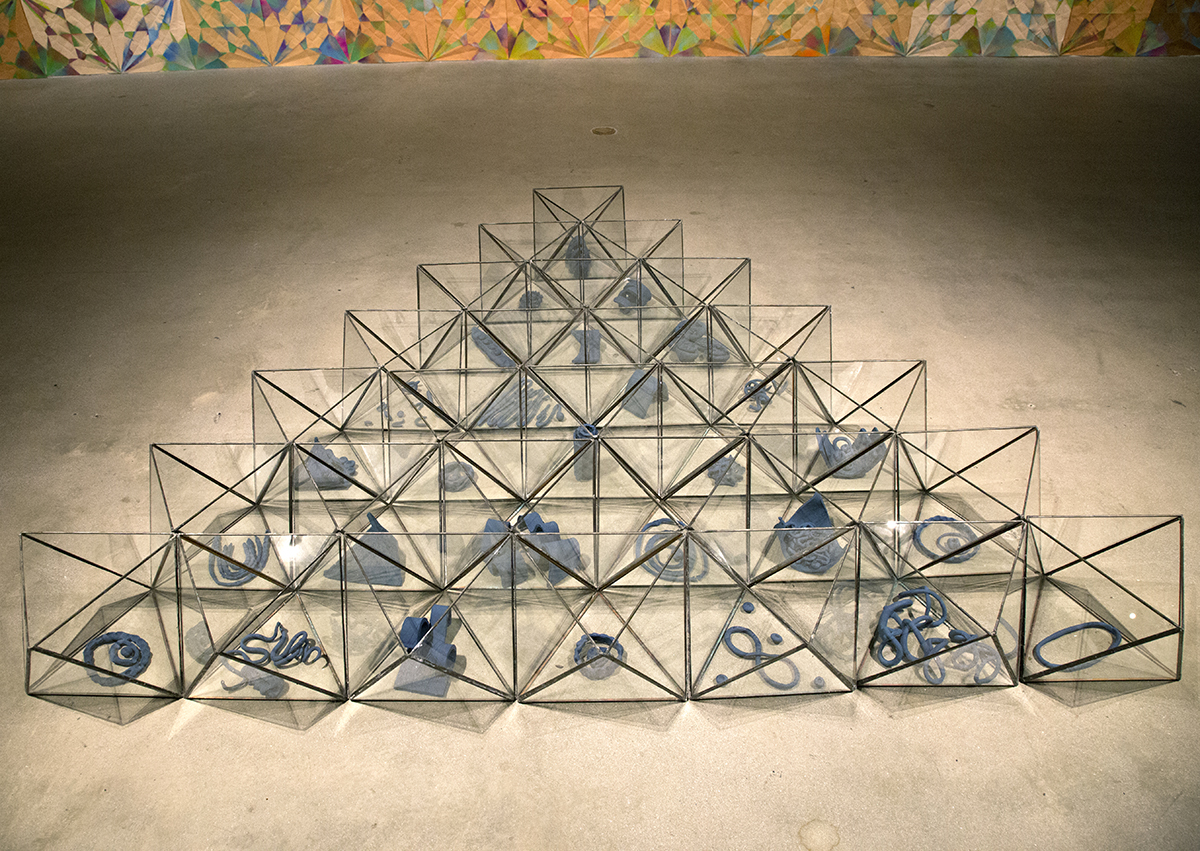

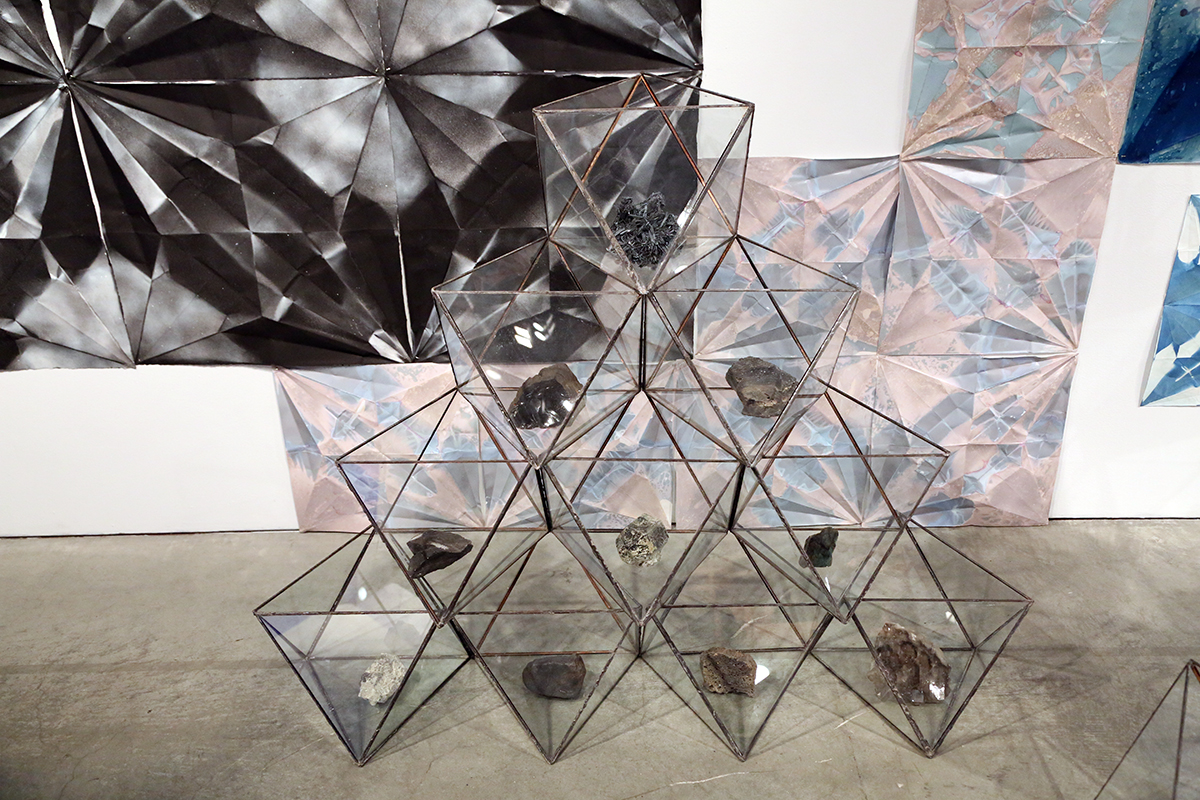

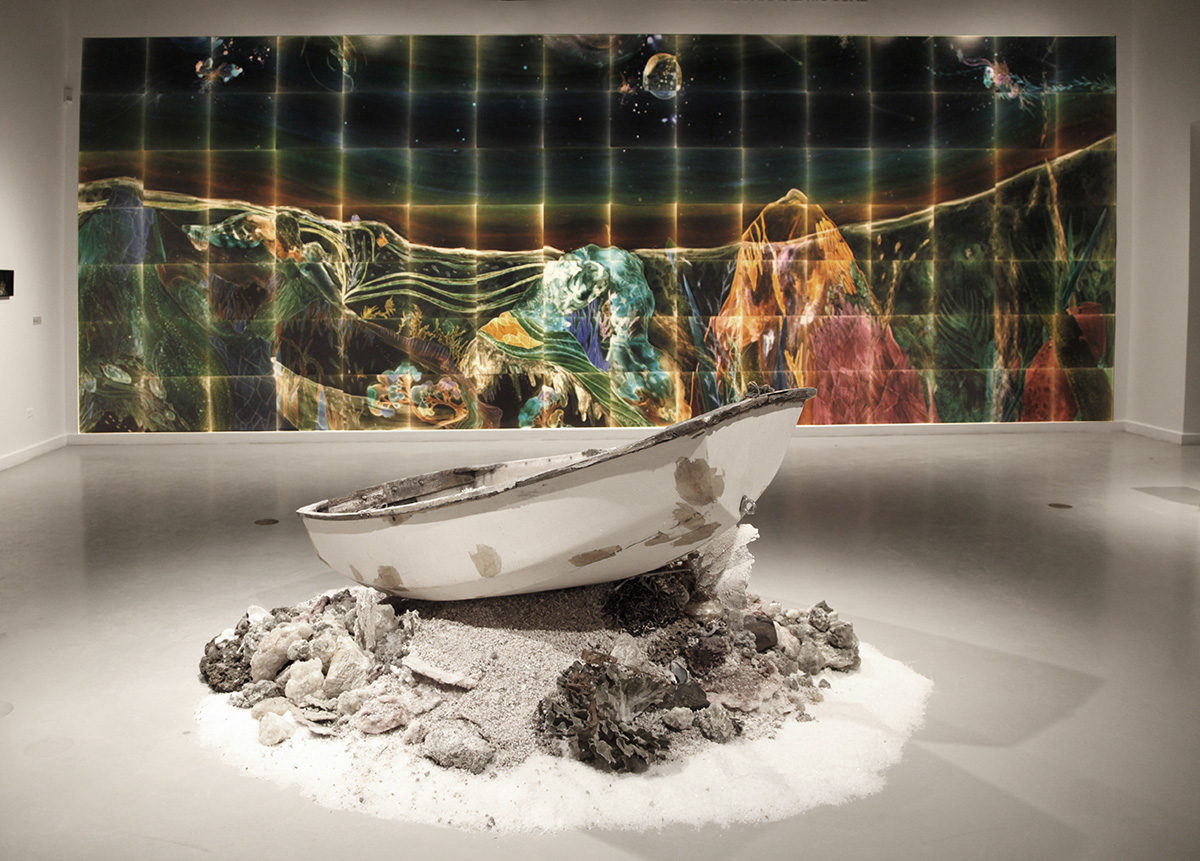

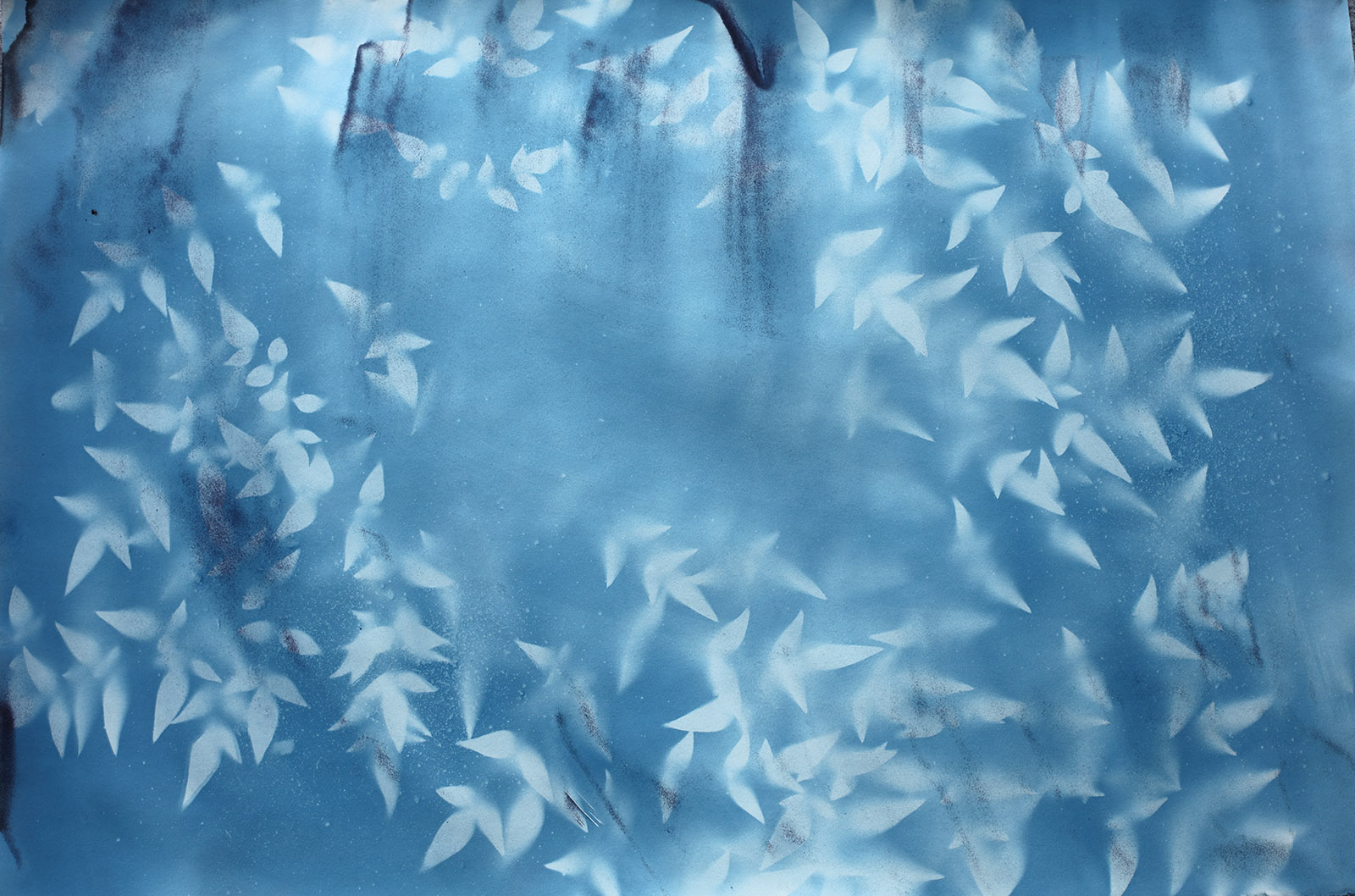

Most recently, in addition to her photo-based works and drawings on Mylar, Nguyen has been producing salt-crystallized cyanotypes, gem-shaped stained glass sculptures, and salvaged objects presented in vitrines. In her series What the Ocean Left Behind, salt-crystallized ocean debris, coral, algae and other vegetation are real found items displayed in glass cases. The Huntington Beach Art Center exhibition includes four of these cases and other works along with Nguyen’s photograms depicting complex ecosystems. In the middle of one room, a salt-crystallized rowboat is stuck high and dry on a mound of brackish seashells, sand, rocks, and coral. Just as in her two-dimensional work, the evaporated contents of the boat chronicle the voyages and revelations of imaginary beings traveling in an unknown expanse of universe. And within that universe Nguyen’s astonishing world illuminates the darkness with a buoyant and poetic ballet of light where we can quietly ponder the intended purpose of our own breathing space that extends from the artist’s thoughts to our own consciousness. Salty residue left lingering on an object or photograph? Maybe it is the remains of a tear mistakenly left behind long ago by a passing Lamenting Orbal.

--John Souza

July 2010